Society

Freepik

While some Muslim-majority countries are blessed with rich endowments of natural resources and are increasingly recognized as leading players in their regions, others are suffering famine, chronic poverty, and disease. This diversity suggests that manifestations of Islam are less important than robust political institutions.

These are turbulent times for the world, and especially for democracy and development. Although humanity's material and technological progress is at its peak, democracy is in retreat, and we are a long way from achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

At first glance, the picture appears especially bleak across the Muslim world, which accounts for one-quarter of the world's population (spread across the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and Africa). But one must not paint with too broad a brush, because socioeconomic and political dynamics across the Organization of Islamic Cooperation's (OIC) 57 members vary considerably. While some are blessed with rich natural-resource endowments and are recognized as leading players in their respective regions, others, tragically, are suffering famine, chronic poverty, and heavy disease burdens.

Given these differences, one must reject the thesis that democracy and development are incompatible with Islamic values. During the Islamic Golden Age, Muslim societies made world-historic progress in the arts, sciences, medicine, philosophy, law, economics, and technology. While the project of democratic and economic development has experienced ups and downs in the modern era, the most severe fluctuations have been in countries still suffering from the legacies of colonialism or past civil wars, ethnic conflicts, and regional disputes. These countries ended up with different political regimes for different reasons, none of which should be assessed through an orientalist lens.

What ultimately matters is good governance. A healthy democracy must have free and fair elections, because that is the only way to institutionalize the bedrock principle of citizens' consent. In Muslim-majority countries with large populations, the proper conduct of elections, followed by a peaceful transition of power without extensive domestic conflicts, is a major achievement in itself.

Whether elections are truly pluralistic and competitive, however, remains an important question. The process for approving candidates needs to be inclusive and adhere to a transparent legal framework. Otherwise, voter turnout, and thus the legitimacy of political institutions, will decline. Fortunately, in a year when half the world's population will go to the polls, Muslim-majority countries so far have passed this litmus test.

But democracy is not only about elections. It is equally important that those who come to power not see themselves as temporarily advantaged players in a zero-sum game. Again, this comes down to good governance. A comprehensive, participatory, and inclusive politics requires respect for the rule of law, human rights, freedom of speech, social cohesion, transparency, and merit-based governance. The Muslim world - regardless of the type of regime - must embrace these commitments if it wants to achieve meaningful levels of development.

Taking Stock

Because political power is inherently prone to abuse, robust institutions are crucial. Otherwise, the cult of the leader can easily override the mechanisms of good governance. As presidential systems have become more common across the Muslim world, executive power has grown more concentrated, straining democratic processes where checks and balances are lacking. Life tenure is not in line with the core values of democracy. Muslim-majority countries urgently need a more progressive approach to this issue.

Since Muslim-majority countries in Europe have more contact with European institutions, they have a more rules-based understanding of the political process. Membership in the Council of Europe and other similar institutions provides a roadmap to democratic transformation, and countries that choose it can indeed achieve positive results in the long term.

But in the Middle East and North Africa - the cradle of civilization in ancient times - the situation is less promising. The 2010-12 Arab Spring generated great expectations, but ultimately failed to drive a regional democratic transformation. Most Northern African countries are now struggling with internal political conflicts, ethnic strife, and economic turbulence, and the situation is even worse in Sub-Saharan Africa, owing to the destructive fallout from ongoing civil wars.

While the US invasion of Iraq and the war in Syria further complicated the region's politics, the Israel-Palestine conflict remains central, and continues to stand in the way of a broader democratic transformation in the Middle East. Israel itself has hampered the adoption of democratic values across the region through its long-standing occupation of Palestinian territory, its unjust support of illegal settlements there, its violations of international law, and its cruelty toward Palestinian civilians - not least in Gaza.

Still, there have been recent positive developments in some of the Middle East's traditional monarchies. The Gulf countries have adopted reforms to strengthen citizen engagement through a number of channels, including - most importantly - local elections. Saudi Arabia's steady liberalization of social and economic norms - including allowing women to participate at all levels of political and economic life - may be the start of a sea change for the Kingdom and the entire Gulf region.

Of course, while Saudi Arabia is embracing modernization, women and girls in Afghanistan have been denied access to secondary education and deprived of other rights since the Taliban's return to power. But make no mistake: this inhumane treatment has nothing to do with Islamic values.

And while Afghanistan will remain a source of insecurity for the region and the world, the situation across Central Asia is more promising. These Muslim-majority countries have come a long way, both politically and economically, since achieving independence three decades ago. Overcoming their Soviet pasts, they have become key geopolitical players in the region and beyond. Uzbekistan, especially, has made remarkable progress toward political reform and opening its economy.

Finally, Muslim-majority countries in Asia - with their large populations - will need to consolidate democratic institutions if they are to continue meeting their citizens' demands and manage the inevitable tradeoffs that accompany economic development.

A Shared Destination

Despite its diversity, the Muslim world faces common challenges, including deteriorating democratic standards, backsliding on the rule of law, constraints on freedom of expression, economic inequalities, corruption, potential ethnic or sectarian conflicts, and security vacuums that heighten the risks of terrorist activities.

To address these problems, governments need to build a climate of trust and public welfare. A good place to start is to empower the education system to raise new generations that prioritize human rights. Only by addressing root causes can we staunch the outflow of millions of people seeking better opportunities elsewhere. Indeed, embracing the values and institutions necessary for democracy and development is the most promising solution to the irregular migration that now dominates Western countries' domestic politics.

Yes, good governance requires robust institutions and financial means, not just rhetorical commitments. Fortunately, with a well-considered, policy-oriented approach, these ends are fully available to any society, Muslim-majority or not, that chooses to pursue them.

From Project Syndicate

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

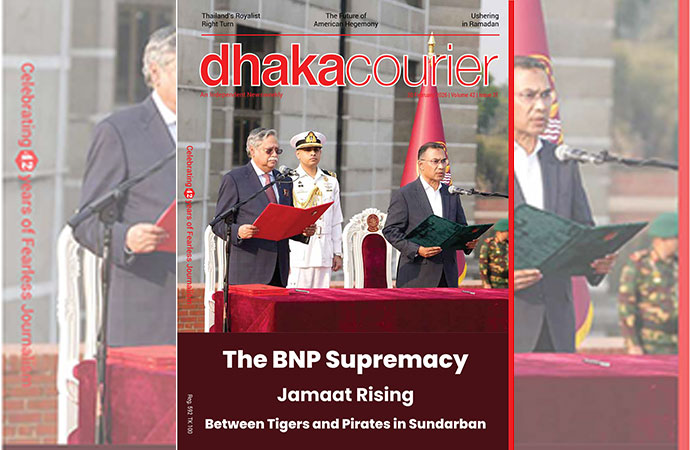

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury