Global

Syrian citizens stand on a government forces tank, that was left on a street, as they are celebrating during the second day of the take over of the city by the insurgents in Damascus, Syria, Monday, Dec. 9,2024. Photo: AP/UNB

In the Middle East, religious and sectarian divisions perpetuate political tyranny, entrenched bigotry, and extremist fundamentalist projects, making the aspirations of the Arab Spring seem as distant as ever. But despite the tragedies of the past few years, recent developments finally offer hope for lasting change.

In principle, initiatives aimed at promoting reconciliation between religions and sects should be welcomed wherever they appear. But when they are backed by regimes whose involvement is more performative than genuine, they are more likely to breed cynicism than effect meaningful change. Moreover, framing the issue as a "reconciliation between religions and sects" can be misleading. Usually, what is really needed is not reconciliation between religions, but reconciliation between institutions and regimes that seek to define religious meaning for each faith and sect.

Religious belief is a universal phenomenon, though it is expressed through many names. It encompasses all the rituals, rules, and forms of worship through which humans foster a spiritual connection between Creator and created, cultivate morally balanced individuals and communities, and link human existence to a higher purpose beyond materialism and time. The tragedy arises when religion and sectarian identities are exploited as tools in the pursuit of worldly power. Wherever this happens, democracy becomes more difficult to establish or sustain.

The Syrian Spring

In the Middle East, religious and sectarian divisions are deeply intertwined with political tyranny, entrenched bigotry, and fundamentalist extremism. These divisions have been fueled by the legacy of colonialism, ongoing foreign political interference, and local dictatorships, which have transformed sectarian and religious identities - Sunni and Shia, as well as other religious and ethnic attachments - into instruments of control and oppression that serve to suppress struggles for freedom.

Yet despite such divisions, history shows that the Middle East has often exhibited a deeper level of harmonious coexistence than many other regions. This deeper historical experience reminds us that peaceful coexistence is always possible. We must draw on this positive legacy to rebuild coexisting societies and nations free from tyranny, fanaticism, and external interference.

Consider Syria. For decades, the country suffered under a dictatorial regime that relied on its founder's Alawi sect to consolidate power, then masked its authoritarianism and divisiveness behind the façade of Arab nationalism (Ba'athism). Bashar al-Assad's regime resisted the revolution that began in 2011 by collaborating with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Russia, Shia militias from Afghanistan and elsewhere, and Hezbollah. These outside forces all contributed to the horrific atrocities committed against the Syrian people, taking hundreds of thousands of innocent lives, displacing millions more, and reducing entire cities to rubble.

Through it all, the regime relied on the rhetoric of sectarian mobilization, sowing divisions as a survival strategy. Yet, despite daunting challenges over the past 13 years, the Syrian revolution ultimately triumphed. Assad's flight to asylum in Russia leaves the Syrian people with the formidable task of rebuilding their country and confronting the legacies of repression, torture, imprisonment, war, and toxic sectarianism.

In this context, the recent explosion of violence is dismaying, but not particularly surprising. Reports indicate that clashes between Syrian security forces and militants loyal to Assad have resulted in the deaths of 1,300 people - most of them civilians.

Some are attempting to frame these events as a sectarian conflict between Alawite militias and the new Syrian leadership, portraying it as a struggle between an Alawite minority and a Sunni majority. But this narrative is both misleading and dangerous. What is unfolding in Syria is not a sectarian war; it is another front in the counterrevolution: an effort led by Iran, and possibly the United Arab Emirates, two regimes that have long opposed the Arab Spring and the legitimate aspirations of the region's peoples for freedom and dignity. The remnants of Assad's regime, bolstered by Iranian support, are determined to prevent the emergence of a stable Syria under new leadership that represents the will of its people. Instead, they seek to plunge the country into yet another devastating civil war, mirroring the ongoing catastrophe in Sudan.

Yet there is a fundamental difference this time. The Syrian people have learned painful and profound lessons from the tragic experiences of other Arab Spring countries. They are more determined and better prepared to protect themselves from falling into the same disastrous cycle that engulfed Sudan or Libya.

Syrians continue to take steps toward establishing a new political order that redefines national identity. The recent agreement between the government in Damascus and an alliance of Kurdish-led militias is a major breakthrough. Syria's Kurdish minority will be formally recognized as "an integral part of the Syrian state," bearing the same "rights of all Syrians to representation and participation in the political process."

That is indeed the goal: to transcend the old divisions. Syrians stand on the threshold of a significant transformation, following a revolution in which the victors refrained from pursuing revenge or retribution. This initial display of sectarian, ethnic, and religious tolerance was remarkable, and it should remain the goal, because it is the prerequisite for stability and the reconstruction.

To build on the foundation that the revolution laid, Syrians will need to contain retributive violence and build the state capacity needed to maintain order. It is also essential for the international community to provide economic support to the Syrian people, not least by lifting sanctions that harm ordinary Syrians. Continuing these sanctions not only exacerbates needless suffering, but inadvertently rewards the remnants of Assad's criminal regime. Such measures risk undermining the Syrian-led political transition and could jeopardize the entire transitional process toward a stable and free Syria.

In the newly envisioned state, all citizens will be recognized as Syrian, regardless of whether they are Alawite or Druze, Sunni or Shia, Kurdish or Arab. This goal alone marks a historic turning point. Efforts to chart a democratic transitional course in Damascus - despite inevitable social tensions and the need for reconciliation - offer hope for the entire region. I am confident that Syria's transformation into a democratic state with equal citizenship for all is imminent, and that its example will offer a model for others.

The Struggle Continues

Meanwhile, in neighboring Lebanon, the past year and a half of regional warfare has weakened Hezbollah's influence, finally breaking the political stalemate and allowing for the election of a new president (former army chief Joseph Aoun), a post that had remained vacant for more than two years. Most Lebanese seem eager to reclaim the rule of law and revive the political life that was circumscribed by Hezbollah's militarized sectarianism.

Then there is my own country, Yemen. In 2013, following the peaceful revolution that ousted Ali Abdullah Saleh, we, too, stood at the threshold of a historic democratic transition. The country was preparing for a referendum on a new constitution and elections as part of a consensus-driven process. But a coup, launched by the Iranian-backed Houthis, plunged us into a devastating war and deepened sectarian divisions. Interventions by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates against the Houthis only added to the turmoil.

Despite being enemies, the Houthis and the intervening regional powers had a common goal: thwarting democratization following the Arab Spring. The past decade-plus of war has been about extinguishing any hope of establishing a modern, pluralist democratic state. The Houthis, with their sectarian rhetoric and foreign agenda, sought to impose a reality that would make such a state impossible.

Yet the Yemeni people remain committed to their fight against Houthi sectarianism. They know that the only promising path forward lies in restoring the national state and the transitional framework that would have guaranteed rule of law, equal citizenship, and new institutions. Amid the region's shifting dynamics, Yemen may find hope in the waning influence of the sectarian Iranian axis in Syria and Lebanon. This new reality offers a historic opportunity for Yemenis to reclaim their country and rebuild it on strong democratic and national foundations.

We would do well to remember how we got here. The counter-revolutionary wars against the Arab Spring led to state collapse and the rise of transnational militia groups across the region, undermining many emerging democracies. In Egypt and Tunisia, for example, coups derailed democratic transitions and brought back autocratic leaders who ruthlessly crushed any opposition. In Sudan, the path to reconciliation has been hindered by regional powers hostile to democracy, many of which are now exploiting Mohamed Hamdan "Hemedti" Dagalo's militias to further their own agendas.

Still, I believe that we could be witnessing the arrival of another Arab Spring. The profound moral victory of the Syrian revolution will re-inspire many across the region to persist in their fight for freedom and for states that guarantee basic rights and justice.

Lessons Learned?

While the West has long claimed to support democracy and coexistence in the Middle East, its policies have often implied otherwise. Perhaps we should not be surprised. It was Western powers - primarily the British and the French - who divided the region into artificial political entities, deepening sectarian and ethnic divisions and sowing the seeds for so many of today's conflicts. Western interventions in the region have openly fostered sectarianism ever since.

For example, immediately after the US invasion of Iraq, many hoped that Saddam Hussein's removal would mark the beginning of the region's transition to democracy. But the opposite occurred, because the American occupation established a sectarian political system based on quotas among Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish groups. This led, predictably, to separate zones of control, bloody conflicts between Shia and Sunni groups, and ultimately national fragmentation.

Instead of promoting a unified national identity, Western powers emphasized religious and sectarian affiliations, deepening divisions and entrenching sectarianism as a permanent aspect of governance. Now, whenever discussions arise about providing "guarantees for minorities," they are seen as external attempts to shore up politically useful sectarian identities, rather than as genuine appeals for equal rights under a unified national state.

Indeed, many defended the half-century-old Assad regime on the grounds that it protected minorities. Even when it collapsed, the first reaction from many foreign diplomats was to call attention to Syria's newly vulnerable minorities. Such demands may have been well-intentioned, but they overlooked the reality of the situation. Those who have suffered decades of exclusion and repression constitute a vast majority. They are the ones who are most in need of solidarity and support. Minority rights will never be firmly secured unless those of the majority are, too. "Stability" based on sectarianism is always an illusion.

Achieving genuine reconciliation and reform requires eliminating tyranny, which is the real barrier to unity. Relying on dictators to maintain civil peace or protect minority rights has consistently failed, because these regimes rely on a strategy of fomenting divisions. Once autocracy has been overcome, true reconciliation can begin by dismantling exclusionary institutions, renouncing extremist ideologies, and confronting the politicization of religion. Only then can relationships between individuals find a footing on common ethical principles.

To that end, individual identity should be defined by citizenship within a state that upholds the rule of law and treats all people equally, regardless of religious or sectarian identity. Democracy is about more than just elections; to sustain itself between elections, it must foster coexistence and respect for differences. While oppressive regimes exploit sectarianism as a means of undermining social cohesion, democratic systems must do the opposite, ensuring that religious and sectarian affiliations remain personal matters.

A state built on equal citizenship allows for political differences to be managed within shared institutions, rather than through sectarian conflict. As such, it represents the sole pathway to achieving lasting stability in the region. Moreover, national dialogues, like the one underway in Syria, will bear fruit only if they are grounded in pluralistic principles and structured to counter external agendas that seek to exploit divisions.

Finally, since this is the Middle East, any discussion of interfaith coexistence, democracy, and political pluralism must account for the Palestinian issue, which is ever-present, shaping every idea and framing every conversation about the region's future. The latest war in Gaza - with its widespread destruction and tragic loss of life - presents us with a moral and humanitarian imperative. Such a large-scale human tragedy obliges the rest of the world to reach out to the Palestinians, not merely to alleviate their suffering but also to assist in rebuilding their homes, infrastructure, and aspirations.

Palestinians deserve dignity, security, and freedom, and it is a profound shame for humanity that their suffering continues. Transformative change can occur only after the occupation and oppression have ended. Peace in the region depends on the recognition of Palestinians' right to self-determination through the establishment of an independent state based on the 1967 borders. Every effort to support this right is an investment in a more just, democratic, and stable Middle East.

From Project Syndicate

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

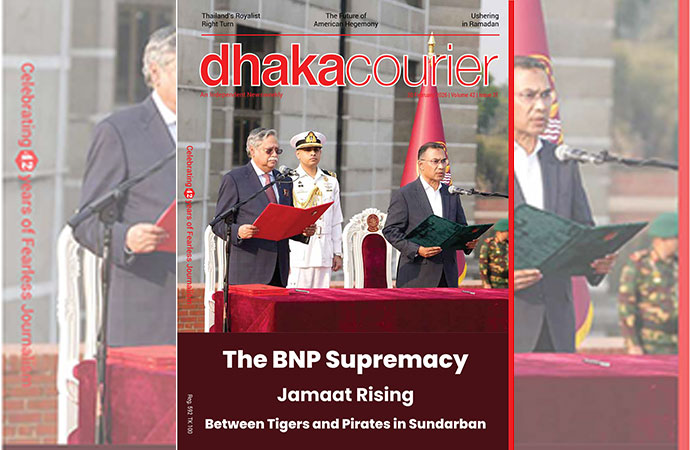

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury