Column

Image: Courtesy

Bangladesh came to mind when I read a recent interview in The Guardian with the Irish writer Claire Kilroy, where she speaks of reading James Joyce's Ulysses as a teenager. (Reading Ulysses as a teenager? Gosh! All teenagers are equal but some teenagers are more aged than others if they have read Joyce. I was not one of them. But anyway...) Kilroy, now 51, says that she read Ulysses because it was so intimately connected to her sense of self-worth. "Ireland felt like a hopeless place when I was growing up. Our geography book taught us that we were the sick man of Europe. My generation, like all the generations before me, was raised for export. We were cheap labour, of little worth. But we could write. We were artists. Art may have been all we had, but what a thing to have."

Joyce's masterpiece is modelled, of course, on the travels of Homer's Odysseus, the hero of his epic poem, the Odyssey, a name Latinised into Ulysses. The mythological wanderings of Ulysses are transformed into contemporary materiality in Joyce's novel through subtle correspondences and obvious parallels that affirm an unending human quest for existence even as it runs up against modern concerns such as antisemitism, sexual acceptability, colonial rule (the British in Ireland), and corresponding nationalism (the Irish in the British Isles). The insistently allusive nature of the novel establishes it firmly in a classical tradition that stretches from ancient Greece to 20th-century Dublin. The novel's stream of consciousness technique allows Joyce ample space to recall ancient experiences and transfigure them into modern lines.

Now to return to the Bangladeshi connection with the export of people and the import (in the sense of importance) of ideas.

It is obviously not true that Bangladesh raises its people for export in the way in which Ireland was forced to do historically because of conflict, famine and a severe and prolonged lack of economic opportunity. The population of Ireland is just over 5 million but, in one account, an estimated 50 million to 80 million people around the world possess Irish roots. They are found mainly in English-speaking countries such as Great Britain, the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, but they are present also in Argentina, Mexico, Brazil and Germany.

By contrast, Bangladesh, with a population of more than 170 million, accounts for a diaspora of about 7.5 million. Numerically, there is no comparison with Ireland.

However, there is a cultural connection. Just as the global Irish diaspora has contributed to the material preservation of Irish culture back home, so have the Bangladeshi diaspora's valuable remittances, generated by manual workers notably, helped to sustain the national economy which empowers Bengali culture to thrive in Bangladesh. In both cases, human "exports" underpin the materiality of domestic cultural production.

Just as Joyce situated his contemporary Ireland irrevocably on the Graeco-Roman map of providential Europe in (and beyond) which his fellow-Irish were dispersed, innumerable Bangladeshi writers, intellectuals and journalists globalise their country today because of the expansion of the domestic economy supported by Bangladeshi labour excelling in lands and climes not its own.

Let me give you an example.

Roman Holiday

My family and I visited Italy two decades ago. In Rome, as we stepped off the tourist bus near the Coliseum, a young man came up to sell us handkerchiefs. I bought a couple, but not before asking him about himself and his family back home (in Bangla, of course). "Bhaiyya," he said, "do not be ashamed of me." I looked at him, waiting to give him an Epaar Bangla-Opaar Bangla slap. "I am selling these today, but I shall not do so forever. Bangladeshis are not born to sell handkerchiefs to foreigners in Rome forever."

I asked him to draw closer. He hesitated, noticing my trembling right hand coming up eagerly. But then he drew closer. I embraced him and said: "I shall slap you if you ever say that again. I shall return to Rome to slap you. And then I shall wipe your eyes with one of your handkerchiefs. The other one I shall keep for my own eyes."

It is a pity that globalisation revolves so closely on the free export and import of capital and talent but not on human labour. The reason is simple from the point of view of economics: The global supply of unskilled labour exceeds the global demand for it, whereas the demand for skilled labour exceeds supply.

However, the foreign workers (Bangladeshi or otherwise) who build homes around the world do not get to live in them. The foreign domestic workers who run others' homes and raise others' children in the absence of busy "Master" and busier "Ma'am" return to their own homes one day, when their own children have grown up beyond familial recognition and their husbands are no longer their own. Immigrant children who sell flowers or play the accordion for a few cents in Athens never get to be a part of classical Greece's legacy to the world.

But when their Odyssean journeys are over, these workers return home to the countries that they have helped to build. Exported from the lands of their birth, they return as richer imports. In the meanwhile, their Homeric journeys have helped to keep their national cultures anchored at home, where many a Joyce competes to write the next Ulysses. Foreign workers are the real mainstay of the globalising world.

That is why, even here in Singapore, which is a much better place of temporary economic exile for foreign workers than countries elsewhere, I make it a point to be especially nice to them, whether they are Bengalis from Bangladesh or Tamils from India or Chinese from China or anyone else from anywhere else.

After all, I arrived here as a foreigner here in 1984, armed with only my degrees, my professional affiliations, and a suitcase full of travelling dreams. I was and remain a worker like these later arrivals. True, they do not have my degrees, but it does not matter. I have become older and more cynical: It does not matter. The world has changed: That, too, does not matter. What matters is that, even as a citizen, the itinerant worker has not disappeared from the settled compactness of my being.

So I invite my friends from the global diaspora of work to share a tear, a thought and possibly a smile with me if they please.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow at the Cosmos Foundation. He may be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

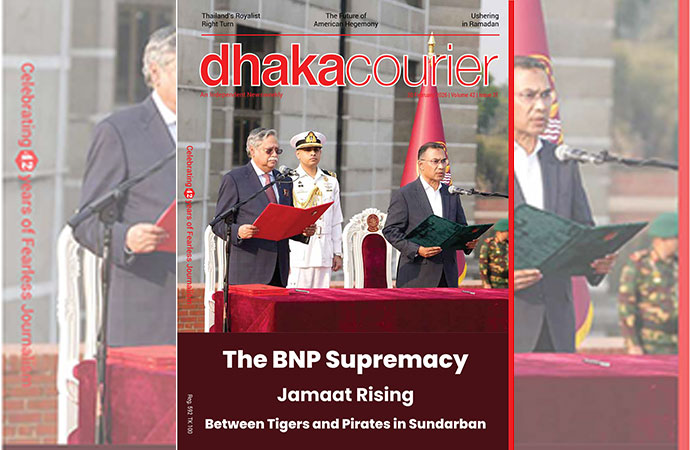

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury