Society

Image: ResearchGate

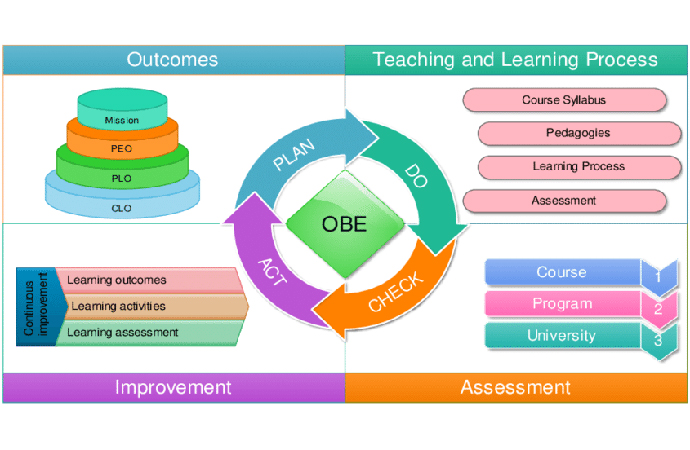

Outcome-Based Education (OBE) has become increasingly common in many universities across Bangladesh. Three key aspects of OBE were described in the teaching and learning guide: establish the learning outcomes; teaching to make it more likely that the majority of students achieve the outcomes; and use authentic assessment to estimate how effectively the objectives have been met. It is widely regarded as a progressive system that emphasizes practical skills and aligns education with standards. It is assumed that the OBE approach encourages active learning. By setting clear learning outcomes, OBE helps teachers design courses with purpose and direction, while enabling students to understand exactly what they are expected to achieve.

OBE requires every course, class, and exam to follow fixed learning outcomes. While such an arrangement may appear organized, it limits the deeper purpose of higher education. In countries where OBE has been more successful, the system is supported by flexible curricula, strong teacher training, a lower teacher-student ratio, and abundant resources-allowing students to think critically, question freely, and explore ideas. For us, the rigid structure often forces teachers to design courses backward from fixed outcomes rather than building knowledge gradually. This makes teaching feel mechanical, learning superficial, and students and teachers both more focused on ticking boxes than truly grasping the subject. The question is, outcomes that are poorly stated will not be "fit for purpose" and could cause students to become confused about what they are supposed to learn. Moreover, assessment must closely align with any predetermined results, according to "constructive alignment." This is a limitation of outcomes as well.

In fact, OBE resembles an old tonic in a new bottle. Nothing is truly innovative in OBE except for the organization and preservation of documents. To be honest, OBE is not currently the most necessary component of our university education system. Our main challenges are the outdated curricula, lack of research facilities, teacher shortages, and limited classroom engagement. Rather than helping, OBE simply adds more stress for both teachers and students. We focus more on documentation, i.e., program outcomes (PO) and course outcomes (CO) mapping, than on improving education quality. Unlike China or the U.S., our system lacks the support OBE needs, making it feel out of place and ineffective. OBE increases workload but brings no significant academic improvement.

The most concerning aspect is the pressure on both students and teachers. Students are repeatedly weighed down with outcome-based assignments, leaving little space for creativity or independent inquiry. Meanwhile, faculty members are worn out from the constant administrative tasks of documenting outcomes, mapping course goals, and generating performance metrics, often at the expense of meaningful mentorship and research. In a country where university research output already faces challenges, these shifts further sap resources from academic growth. In fact, OBE is deteriorating the quality of education and research among universities.

According to OBE, teachers must always teach the same material to all of their students in the same manner; this is known as rote learning. It focuses on the necessity of output standardization rather than the needs of the students. I think about the goal of education as stated by famous educator John Dewey at the beginning of the 20th century in order to comprehend why OBE is failing so miserably. He posed a straightforward query: When we discuss teaching, do we mean rote facts and predetermined answers, or are we referring to the capacity for original thought and invention? Dewey's query establishes a contrast between rote learning and creativity. Although each of these two items has a specific role in the educational setting, OBE only effectively supports one of them.

According to critics, creating learning outcomes can be challenging and time-consuming. OBE was tested in primary and secondary education systems across several countries, particularly in the USA, South Africa, and Australia; however, it faced significant public opposition. The criticism of OBE in the United States included a loss of essential educational material due to the excessive emphasis on the educational process and the substantial time commitment required of teachers for assessments. In Australia, it presents challenges to assessments and fails to provide basic skills in math and science, as evidenced by South Africa's experience.

To conclude, our universities should concentrate on solving real issues like improving teaching quality, modernizing course content, and supporting research before adopting complex rule-based systems like OBE. The current focus on results as a universal solution for assessing educational effectiveness needs to shift; we must prioritize a learner-centered approach to education once again. Indeed, OBE is more suitable for secondary schools and polytechnical institutions rather than the university level. What works well in other countries may not fit our situation. For us, OBE has added more complications than solutions. If we truly want to see progress in higher education, we need changes that reflect our own needs, not borrowed ideas that do not match our reality.

Mohammad Sultan Mahmud, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Another stress-test for the wo ...

And just like that, the world economy has been thrown into turmoil onc ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan offered to mediate for a new ce ...

Bangladesh flags economic risks of prolonged Middle ..

Bangladesh seeks enhanced cooperation with Argentina

US trade deal discussed with BNP, Jamaat before sign ..

Road Transport and Bridges, Shipping, and Railways M ..