Reportage

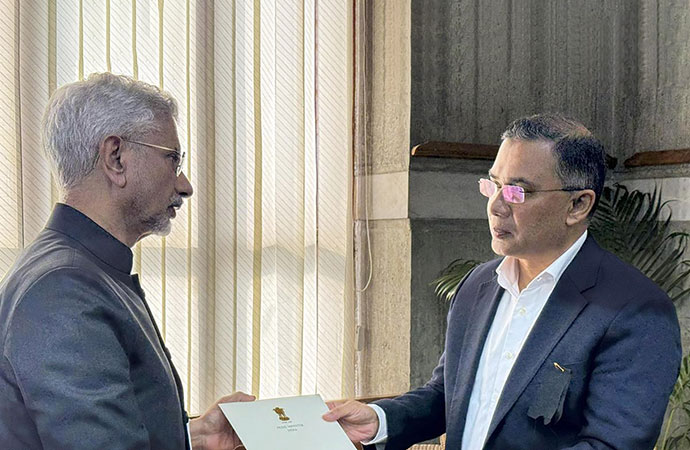

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and BNP Acting Chairman Tarique Rahman. Photo: Collected

It's difficult to know whether even the architects of the July Uprising in 2024 could have imagined that the strong current of "anti-Indianism" that it fed off would've quite gotten us to the point we are at today. The ousted Awami League regime's excessive, in many ways unsolicited and overall detrimental courtship of New Delhi could never have survived the movement that culminated on August 5, 2024. Changes would be rung, that much was clear. What they have descended to, as we head into the closing days now, of the interim government that was installed by general consent of the forces that supported the student-led movement, would not have been foreseen by anyone.

The bilateral relationship with India, not just our biggest but pretty much our only neighbour barring the 70 miles with Myanmar, is today in a state of total dysfunction. We proceed from the point that dysfunction in neighbourly relations is never a good thing - it just isn't. What it reflects on this side of the border, is that among those forces that participated to make the Uprising a success, which was very broad-based, the hardliners have managed to win the day. At least on this very important strand of foreign policy. You can tell who they are by their lack of concern or even by their sense of satisfaction, on full display, at the woeful state of the relationship. And then there are those who are actually driving this whole project, this decoupling if you like, that is really in no-one's interest - which is to say no one's interest that could be fairly described as "public", even less as "national".

Within their own, often nebulous domains, where exist 'deep states' and 'anti-liberation agents', there are of course groups and individuals who are benefiting, and profiting, even profiteering, from all this chaos. India means commerce of course, and as long as you play your cards right, you can monetise almost any position. We've heard of the 'Rahman brothers', detected wide-ranging networks manned by the least likely of characters and feel helpless to explain our capitulation to the crazed narratives of a dissident in Paris. We cannot even question why on earth a dissident who seems preoccupied with nothing else won't set foot back in the land he had fled after his side had apparently won. If this blatant contradiction will not raise suspicion, what will?

But let us choose to dwell in the more real world. The one where even before we could take the time to consider what has been described as an "overture" by the Indian government, a whole host of issues emerge out of the woodwork like worms and soon we're swamped. That gesture of course, was the Indian government's thoughtful and gracious attempt at redeeming themselves in relation to the late Begum Khaleda Zia at her death on the 30th of December. Indian Foreign Minister Subramaniam Jaishankar was the first foreign dignitary to book his flight to Dhaka the next morning for the funeral, and it contributed to turning Begum Zia's janaza into an international event, that featured the closest thing to a reunion of the flagging Saarc grouping in years. Quite apart from the massive turnout of people that turned it into a historic day.

Jaishankar came bearing his impeccable training as a career diplomat, and even a very gracious letter from his prime minister, Narendra Modi, addressed to 'Tarique Rahman sahab', by all accounts. To the extent that India's foreign policy at present can be shaped by the wily Jaishankar, there is a palpable recognition that Delhi acknowledges it messed up somewhere along the line, by adopting its "AL or nothing" policy in Bangladesh. Although a broad narrative of this having persisted since 1971 is prevalent, it was really quite dormant till 2008, when it was revived under the then Congress government in Delhi. The BJP only inherited it in 2014, by which time it was firmly entrenched.

But we cannot overlook the fact that Jaishankar also left without even seeking an appointment with the Chief Adviser to Bangladesh's interim government. This left shades of a snub, and was obviously a decision taken above his paygrade. So while we can appreciate the recognition of its need to engage with the wider Bangladeshi body politic, going beyond AL and its allies, Delhi was also still communicating a message that while it was acknowledging Bangladesh, at least for now, was moving on from the Awami League - and signaling it was willing to work with the most likely next government - it still could not agree with the way that it was ousted.

But how do we go forward from here?

Election off ramp?

According to Michael Kugelman, who heads up the South Asia program at the WIlson Center in Washington, Bangladesh's upcoming election could act as the "off-ramp" that both countries need, in order to reset the relationship. Probably the most prominent and engaged among America's current generation of South Asia scholars/experts, Kugelman has gone into some of the frenzied back-and-forth between the two countries just in the seven days following Begum Zia's funeral, for a weekly newsletter he writes for the readers of Foreign Policy magazine.

In the latest manoeuvring, Bangladesh's interim government banned broadcasts of the Indian Premier League, "one of the world's most prestigious cricket leagues" as Kugelman explains to his mostly American audience. That was just the initial reaction, as it turned out, to the fallout from the Mustafizur affair, in which the Kolkata Knight Riders, owned by Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan, were forced to release the Bangladeshi star Mustafizur Rahman, who had joined the team last month for a record fee at auction.

No valid reason was given for the move to exclude the affable Fizz, who himself didn't seem too bothered by it all. But it was reportedly ordered by India's main cricket body, the BCCI, which is headed by Jay Shah, the son of Amit Shah, whose tenure as BCCI president has been marked by unmistakably nationalist decisionmaking. In a further escalation, for which the reasons remained unclear, Bangladesh then announced that it won't be travelling to play its matches in India during the upcoming T20 World Cup, which is being jointly hosted by India and Sri Lanka.

Kugelman writes: "In a cricket-crazed region where the sport has long been a unifying force (with a few notable exceptions), all of this underscores the depth of India-Bangladesh tensions. Ties became fraught after former Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was ousted in 2024 by mass protests. But the relationship has reached an especially perilous point just weeks before a critical election in Bangladesh on Feb. 12."

He then offers some background to the relationship for his audience that we may peruse, if only to access a detached view, from a more-or-less neutral observer: "The tensions are rooted in part in a core perception that each country harbours toward the other. Bangladeshis believe India has long meddled in the country's domestic politics and foreign policy, while Indians think that Hasina's ouster opened up space for Islamist hard-liners and other actors hostile to Indian interests."

He then describes the current state of play, that we quote extensively below:

"Recent developments have hardened these views. India has hosted Hasina, permitted her to speak out publicly, and refused to turn her over to Bangladesh-reinforcing Dhaka's position. In November, a Bangladeshi court sentenced her to death in absentia for crimes against humanity stemming from the 2024 crackdown on protesters by security forces that killed hundreds of people.

"Last month, an angry mob lynched a Hindu garment factory worker in Bangladesh, where threats to the Hindu minority have drawn concern in India. Prominent Bangladeshi activists have also recently stepped up criticism of New Delhi. One of them, Osman Hadi, was shot last month and died days later; Bangladeshi police allege that two suspects in the killing fled to India, without providing information about their motivations.

"Bangladesh's election nonetheless provides a possible off-ramp. India has expressed readiness to engage with any elected government. The most likely winner, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), has historically had fraught ties with India. But after ending a long alliance with the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami, the BNP is now more palatable to New Delhi.

"After BNP chair and former Bangladeshi Prime Minister Khaleda Zia died last month, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent a warm condolence letter to her son, Tarique Rahman. Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar attended her funeral in Dhaka. India appears to be signaling a new approach to a potential BNP-led government.

"For his part, Rahman-who may be Bangladesh's next prime minister-has called for unity, which may be an indirect way of assuring India that his government would work to protect Bangladesh's Hindu minority.

"However, the question is if domestic political factors could limit each country's willingness to extend an olive branch. Powerful Islamist actors in Bangladesh reject engagement with India, limiting the political space for any new government in Dhaka. There is less risk for Modi, who remains extremely popular at home.

"Tellingly, BNP leaders, including Rahman, have used some tough language in recent comments. The party's secretary-general has insisted that good relations with India can only play out on "equal terms." Last October, Rahman said Bangladeshis "have decided that relations [with India] will remain cool. So, I have to stand with my country's people."

"Bangladesh's election offers an opportunity for an India-Bangladesh reset, but only if each government is willing to stomach the political risks."

Role of 'tutored media'

Even at our most generous, we cannot overlook the almost stunningly irresponsible role played by the Indian media, on an almost daily basis, at overwhelming scale, with seemingly footloose editorial standards. It wasn't a Bangladeshi, much less Chief Adviser Yunus, who described India as 'the fake news capital of the world'. Over the last 16 months, as it focused its attention on Bangladesh, we have come to see the full, debilitating force of this unfortunate reality. For the record, it was the World Economic Forum's (WEF) 2024 Global Risks Report, that ranked India highest globally for the risk posed by misinformation and disinformation.

A former chief executive of India's state broadcaster Prasar Bharati, sensationally revealed in an article in the National Herald last week, that much of the vitriol towards Bangladesh flooding the airwaves in India, is the result of 'tutored media'. The article by Jawhar Sircar, in the Congress party's mouthpiece, came down hard on the government in Delhi, for mishandling the relationship over time, including in the immediate aftermath of the Uprising:

"Patient diplomacy in this period could have paid India better dividends than outrage. India's self-righteous wrath conveniently overlooked the fact that minority-bashing is an encouraged national pastime: in the last decade, more than 100 Muslims have been lynched in India (with 25 Muslims killed by mob violence in 2025 alone). The anti-Bangla fury that swept India was led by a largely tutored media.

"The ruling Hindu Right's irresponsibility was evident on social media, where hate was whipped up not only against Bangladesh and Bangladeshi Muslims, but also against Bangla-speaking citizens long domiciled in India."

Playing to the Galleries

There are no doubt well-wishers for the relationship on both sides, who have become rather drowned out in the cacophony of rabble rousers. But the compulsions of domestic politics may be hard to let go, even in the short term. The International Crisis Group flagged the concern recently, in something of an urgent call to policymakers on both sides, issued in the last week of 2025, titled "After the "Golden Era": Getting Bangladesh-India Ties Back on Track".

Domestic politics in both countries could undermine efforts to rebuild ties, however. Fanning anti-India sentiment is a common strategy for Bangladeshi political parties. In India, the Hindu nationalism of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), including its muscular foreign policy and focus on illegal immigration, could increase Bangladeshi resentment of New Delhi.

Elections in the Indian border states of Assam and West Bengal in March-April 2026 are potential flashpoints, as is the looming expiration of the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty. While most political leaders in both countries appear to recognise that better ties would be beneficial, there is also a risk that they could settle into a pattern of acrimony and distrust. The prospect of state-to-state conflict remains remote, but strained relations could manifest in destabilising ways short of war, including violent protests, communal attacks, border killings and insurgent activity. The ICG characterised some of the violence and agitation in the wake of the assassination of Osman Hadi last month as "anti-India violence".

For many years, India has viewed constructive relations with Bangladesh as dependent on the Awami League being in power, to the detriment of both Bangladeshi politics and long-term cross-border ties. If the BNP indeed forms the next government, both sides should grasp the opportunity "to get relations back on to a stable footing," urges Crisis Group.

For its part, they say New Delhi "should seek to go further, however, by strengthening ties across the Bangladeshi political spectrum - not only with the post-election administration, but with other parties as well - and further develop people-to-people links and economic connections". While India will logically put its own economic and security interests first, it should also ensure that its initiatives are mutually beneficial and consider domestic sensitivities in Bangladesh. It should also begin planning, says Crisis Group, "a charm offensive" of good-will gestures and new policies that it could present to the incoming government, starting with the reversal of visa restrictions imposed in August 2024.

Bangladeshi political parties, especially on the campaign trail, should resist the temptation to use anti-Indian sentiment to win votes in the forthcoming elections, according to Crisis Group. "Such electoral tactics would reinforce the widely held belief in India that the major parties contesting the polls are inimical to its interests, particularly on security - a view informed by historical precedent," they say.

In keeping with its realist ethos, the organisation reminds Bangladesh that any incoming government should seek to "reciprocate New Delhi's overtures, adopt a balanced foreign policy, keep a lid on insurgency and extremism, and do more to curb cross-border smuggling."

And that's your shopping list.

An Early Test

Bangladeshi and Indian engineers are currently monitoring water flows at key points to ensure compliance with the 1996 Ganges Water Sharing Treaty. This is the final year of the 30-year treaty, under which from January 1 to May 31 each year (the designated 'lean' season), water from the Ganges at Farakka in West Bengal is shared between the two countries.

The agreement stipulates that if the river flow at Farakka is up to 70,000 cusecs, the water is split equally. If flow exceeds 70,000 cusecs but is below 75,000 cusecs, Bangladesh receives a maximum of 36,000 cusecs, with the remainder going to India.

If flow surpasses 75,000 cusecs, India retains 40,000 cusecs, and the rest is allocated to Bangladesh. Allocation is calculated in ten-day intervals.

A guaranteed flow of 35,000 cusecs is ensured for each country in alternating ten-day periods from March 11 to May 10, when river flow is typically lower. The current treaty expires in December 2026.

Four Bangladeshi engineers are stationed at Farakka in India to measure river discharge, while two Indian engineers are in Bangladesh at the Hardinge Bridge to verify that allocated water reaches the country.

Joint River Commission sources said representatives from both countries have been present at the monitoring points since January 1 and will continue until May 31.

The agreement, signed on December 12, 1996 in New Delhi by then Indian prime minister HD Deve Gowda and then Bangladesh's then-prime minister, Sheikh Hasina.

Bangladesh and India share 54 rivers, but only the Ganges has a formal water-sharing agreement. Negotiations over Teesta River water have long stalled due to objections from West Bengal's Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee.

Relations between the two countries have heated up since the fall of Hasina's government in August 2024. However, Joint River Commission meetings have continued, including two in Dhaka, one in Delhi, and one in Kolkata, most recently on 9 September in New Delhi.

Commission sources said both countries have agreed in principle to renew the Ganga water-sharing treaty. Formal negotiations are expected to begin once the elected Bangladeshi government assumes office.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

From the British High Commissi ...

From December 26-30 of last year, WildTeam had the honour of hosting H ...

Why Southeast Asia’s online sc ...

Cambodia’s arrest and extradition of a powerful tycoon accused o ...

LC openings surge as dollar crisis eases, but settle ..

US President Donald Trump has been discussing "a ran ..

Delhi and Dhaka need to find an off ramp

Moin re-elected DCAB President; Emrul Kayesh new GS