Politics

Photo: AP/UNB

The Indo-Pacific lacks many of the institutions and alliances that are now teetering elsewhere. But as instability proliferates worldwide, they are urgently needed, and the region's leaders should commit to realizing the late Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s vision of an Indo-Pacific that is open, united, stable, and secure.

We are living in an age of global disruption. Supply chains are being reconfigured to avoid dependence on any one producer or country. Trade ties are being upended by high and unpredictable tariffs (and the threat of more). Longstanding alliances are being strained by doubts about partners' reliability.

Even the most peaceable of neighbors, like those in North America, now eye each other with suspicion. Meanwhile, many of the structures that, however imperfect, delivered relative peace, stability, and prosperity for more than eight decades have been so enfeebled that they can hardly be counted on to function at all.

Of course, not all disruption is bad. As this year's Nobel laureate economists - Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt, and Joel Mokyr - taught us, "creative destruction" is vital to economic dynamism and innovation. But a stable world order is built on creation, not destruction: the formation of strong multilateral institutions, robust alliances, resilient trade relationships, and durable shared norms, founded on the rule of law. The same is true of a stable regional order - a lesson the countries of the Indo-Pacific should take to heart.

As it stands, the Indo-Pacific lacks many of the institutions and alliances that are now teetering elsewhere. This gives regional leaders an opportunity. Like the allied countries after World War II, Indo-Pacific governments can, to borrow a phrase from former US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, be "present at the creation" of a new economic, security, and diplomatic architecture capable of underpinning peace and stability in their vast region.

At a time when revanchism is on the march in Ukraine, and China is seeking hegemony in Asia and beyond, the need for such an architecture is abundantly clear. Where security is concerned, complacency is never warranted. Then-British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain taught us as much in 1938, when he sold out the seemingly faraway Czechoslovakia to Adolf Hitler, triggering a chain of events that culminated a year later in the outbreak of the wider war that Chamberlain thought appeasing Hitler would prevent.

Rather than turn a blind eye to proliferating instability, Indo-Pacific leaders should seek to realize the late Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō's vision of a region that is open, united, stable, and secure. This process should build on existing frameworks, such as the "Quad," comprising Japan, Australia, India, and the United States. Created as a multilateral response to the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the Quad was relaunched (under Abe's leadership) in 2017 as a platform for strategic cooperation, including joint military training and intelligence sharing.

That cooperative framework should now be expanded. Perhaps the most obvious candidate for membership is South Korea, which shares many security concerns with Japan and the US, holds military exercises with both countries, and increasingly shares intelligence with Japan.

Saudi Arabia, which has been engaged in its own powerful military modernization, could also be welcomed into an Indo-Pacific framework. Given the importance of oil exports to its economy, safeguarding maritime security in the Indian Ocean is of paramount interest. Moreover, as the Gulf's dominant economy, it has plenty to offer Indo-Pacific partners, particularly as an entry point for other Gulf states.

No discussion of an Indo-Pacific institutional architecture is complete without the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, which has earned a reputation for advancing its members' economic and political development through cooperation, without impinging on their sovereignty. Over the last year, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, who held ASEAN's rotating chair until the end of October, sought to fortify the 11-member bloc through greater economic and commercial engagement, including increased investment ties.

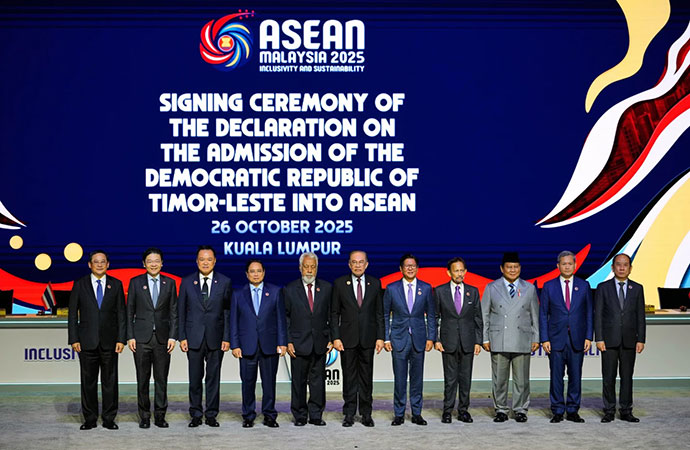

At the same time, Anwar worked to deepen ASEAN's relationships with the rest of Asia, including China, as well as with the US. And he contributed to the bloc's expansion. By welcoming Timor-Leste as a member, ASEAN both reduced the risk of a revival of tensions with Indonesia and extended its influence deeper into the western Pacific.

A bold expansion into the Indian Ocean would open unique opportunities for ASEAN and enhance Indo-Pacific stability. Sri Lanka's accession, for example, would mean gaining an ASEAN outpost in the middle of the Indian Ocean, which would facilitate increased trade and investment ties with India, Africa, and the Gulf. It is thus good news that Sri Lanka, said to be considering a bid for membership in the bloc, is already seeking to strengthen economic and diplomatic ties with ASEAN countries through a Sectoral Dialogue Partnership.

Despite its successes, ASEAN is under considerable pressure. Beyond the civil war ravaging Myanmar, border clashes between Cambodia and Thailand - which Anwar helped to tamp down earlier this year - recently erupted again. But this conflict may not be intractable. A contact group composed of Japan and India, working alongside Anwar, might provide the diplomatic heft necessary to resolve the dispute. As the old adage goes, sometimes the only way to solve a problem is to broaden it.

Other piecemeal efforts to strengthen regional ties are also gaining steam. As punishing US tariffs undermine the competitiveness of Indian exports, Indian firms are increasingly turning to the United Arab Emirates as a bridge to American markets, a steppingstone toward deeper engagement with the Arab world, and a source of capital for Indian industry.

India and the UAE are thus reshaping Indo-Pacific trade in accordance with Abe's vision, articulated two decades ago, of a "broader Asia" formed by a "dynamic coupling" of the region's countries. But fully realizing that vision will require governments to strengthen their commitment to fostering an open, rules-based maritime order, upholding free trade and freedom of navigation, and nurturing economic security and prosperity, from the east coast of Africa to the island nations of the South Pacific.

Indo-Pacific unity is not only possible. In our age of disruption, it is essential. And it is being built the only way it can be: from within.

From Project Syndicate

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Populism strikes again

So it is official now - the Bangladesh national team will not be trave ...

Beijing urges Washington to fo ...

China on Thursday reacted to China-related remarks by the US Ambassado ...

The European Union and the Mercosur bloc of South Am ..

New US Ambassador to Bangladesh raises concern over ..

Gold prices in Bangladesh surged past the Tk 250,000 ..

What is Trump's 'Board of Peace' and who will govern ..