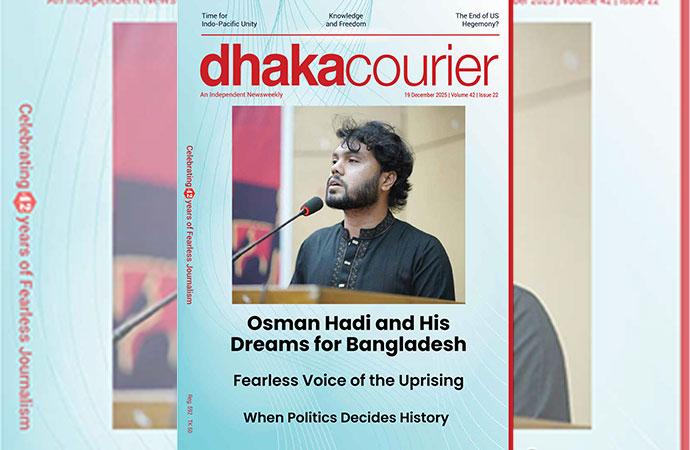

Column

A student at Dhaka University, poses for photograph on the university campus, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, August 10, 2024. Photo: AP/UNB

No matter how the current situation in Bangladesh turns out eventually, it appears that the protesting students have won. Formally, they have won because the interim government includes two of their leaders. Informally, the next general election, whenever it is held, will not be able to ignore the students' imprint on the recent evolution of national history.

That history is tied up with earlier students' movements in Bangladesh and around the world. During the Language Movement of 1952, the February 21 killings caused by police firing transformed a linguistic movement into a political one. The mass uprising of 1969 carried forward the political momentum generated in 1952 till Bangladesh was independent in 1971.

Meanwhile, in May 1968, a signature moment appeared in French history when, early in the morning of the 11th, the police attacked protesting students with tear gas and truncheons. The Latin Quarter, the heart of intellectual Paris, lay in ruins.

But no idea can be destroyed by violence. The students' movement engulfed the rest of France. The largest wildcat general strike in its history shook the French state to its core before it picked up the pieces and hit back. The students' movement did fizzle out, but not without having created a political template for radical change. The July 1968 student-led uprising in Mexico City took over the French mantle briefly.

In the United States, members of the Ohio National Guard fired into a crowd of anti-Vietnam War Kent State University demonstrators in May 1970, killing four and wounding nine others. The students were pushed back, but not before their deaths had inaugurated conservative America's political descent into the Watergate scandal that destroyed the Nixon administration ultimately.

The common motif of these protests and others is the dictum: "Where order is injustice, disorder is the beginning of justice." Bangladesh's protesting students imbibed the spirit of that slogan even if some of them might have been unaware of it. The students were not apolitical - whatever that word means - but many of them were non-partisan: They did not believe that any ruling dispensation, no matter how powerful it is, should enjoy an unquestioned and unlimited lien on power over humans. Students took on the power of the Awami League state: They would have done so even if some other political formation had reduced them to the same level of mental exhaustion in which all that remained and mattered was physical defiance of order.

Disorder may be the beginning of justice, but it cannot be its end. Bangladesh's students demonstrated this logic when they took to the streets after their victory to clear away the debris of violence, literally. They also directed traffic in the absence of a police force that had retreated after having being implicated in brutal attacks on demonstrators.

Extremely important, students encouraged other patriotic Bangladeshis to join them in protecting Hindu homes and places of worship that had come under attack from religious obscurantists or common criminals. Just as students had resisted what they had rejected as illegitimate state power, they were quick to protect their country against the anarchic rule of vandals, vagabonds and opportunists (religious or otherwise) who sought to victimise the minorities because of their support for the erstwhile regime.

Ohama Raaz captures the students' moment in Bangladesh's long hour of change in an article for the Dhaka Tribune. She writes: "The promise of rapid reform and reimagination - be it of country or campus - is undoubtedly appealing, but scuffling during a time of volatility might add fuel to the many fires. History discovers me at a time where I can't comfortably demand all positions of authority to fall, not because I am their proponent, but because for us, the students, both our vulnerability and power lie particularly exposed to exploitation."

She adds: "Demanding (that) mere individuals step down is not enough; we must examine the underlying structures that allow for complicity and corruption, rather than being satisfied by a revolving door of faces. The exploitation of university students and their aspirations must be prevented in order to disable the potential for the state of affairs to veer further towards oppression."

Few could have put it better.

So far, so good, but what now?

The only way to institutionalise protests is to seek power. Power in constitutional terms means political power.

There is talk that the interim government's time in office could lead to the formation of a new political party that would not be related to the conflictual ideologies and contested legacies of the Awami League, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, the Jamaat-i-Islami, the Jatiyo Party or other parties. In some accounts, the new party would be decidedly left-of-centre in what is after all the People's Republic of Bangladesh; and it would be secular while remaining within the constitutional ambit of Islam being the state religion. It might not be a student-led party but it would draw upon the yet unfulfilled aspirations of the young without whom Bangladesh, like any other nation, stands in danger of stagnating and then regressing after a bold but brief encounter with the present.

That is an exciting prospect, but the key question is the extent to which a mass movement can be transformed into a mass party. Normally, it has been the other way around (from the Bolsheviks of Russia to the Congress Party of India to the Awami League of Pakistan/Bangladesh). Also, of course, the mass movement in today's Bangladesh has many strands. The students are the essential strand, but there also are other strands composed of supporters of the very status quo parties with which the new entity would have to contend.

It is too early to say which way the student movement will go.

This is no indictment of Bangladesh. In 1972, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai was asked about the impact of the French Revolution of 1789. He replied that it was too early to say.

As for the students' movement of 2024, it is far, far too early to say anything about its ultimate impact.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow at the Cosmos Foundation. He can be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Populism strikes again

So it is official now - the Bangladesh national team will not be trave ...

Beijing urges Washington to fo ...

China on Thursday reacted to China-related remarks by the US Ambassado ...

The European Union and the Mercosur bloc of South Am ..

New US Ambassador to Bangladesh raises concern over ..

Gold prices in Bangladesh surged past the Tk 250,000 ..

What is Trump's 'Board of Peace' and who will govern ..