Featured 2

“Let me forget that I was born in the dust; there is no dust within me…” ‘Chandalika’, Rabindranath Tagore

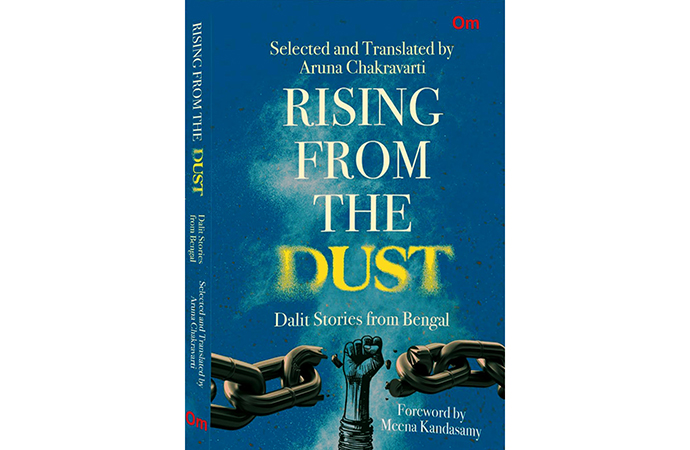

Selected and Translated by Aruna Chakravarti

In hand is a compilation of twelve short stories from both female and male Dalit caste and non-Dalit writers. Dalits have also been categorized as a 'Backward Caste', 'Untouchables' and are subject to systematic social exclusion. The collection presents a painstaking perception in the translation from Bangla into English. We have an immensely praise-worthy undertaking by Aruna Chakravarti, a Kolkata Bangali writer and translator residing in New Delhi. As a reviewer, I quote Chakravarti in her 'Translator's Note' in her book: "shakes the reader both intellectually and emotionally." She has in 'Rising from the Dust' achieved both. The first short story 'Fortress' written by Manoranjan Byapari, shook me to the core. This is a raw and unsettling read. The ability of the translator to transfer the Bangla text into such impactful English is both evocative and haunting. How to convey desperate nuances? She has selected and translated chilling and compelling writing, painfully profound till the last paragraph. We are reading a masterful handling of the tone and meaning conveying Bangla expressions. Every day expressions in one language do not easily convey the essence and atmospheric content of the written output.

Lives are 'Rising from the Dust' at times. However, at what cost? Life? Is this salvation? Is heart break or surrender survival? These short stories linger long after the book closes. How do short stories, a form of literature convey in such a short space the intense context of 'Rising from the Dust'? It is an immensely impactful literature achievement by the writers.

Aruna Chakravarti is the recipient of numerous prestigious literary awards; Vaitalik Award, Sahitya Akademi Award and Sarat Puraskar. Her first novel 'The Inheritors' was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers' Prize. Her second, 'Jorasanko' and its sequel 'Daughters of Jorasanko' remain best sellers. In fact, upon a second visit to Rabindranath Tagore's family home in Kolkata, I was told by a young guide that "the footfall of visitors to Jorasanko has increased immensely since the publication of the above two books." (I have reviewed both.) 'Suralakshmi Villa' received 'Novel of the year (India 2020) by Indian Bibliography published in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature U.K. 'The Mendicant Prince' (2022) is known historically in both Bangladesh and West Bengal. It is inspired by the legendary Bhawal Sannyasi case. (Also have reviewed.) Her translated works include an anthology of songs from Rabindranath Tagore's 'Gitabitaan', Saratchandra Chattopadhyay's 'Srikanta' and Sunil Gangopadhyay's 'Those Days, First Light and Primal Woman: Stories.'

The book title is 'Rising from the Dust' Dalit Stories from Bengal. And not 'Risen from the Dust.' Chakravarti's book is reflective of the social dictates, the personal sacrifices and even the loss of lives in an environment that despite every initiative of the individual; continues to impact. The selection of stories portrays the patriarchal societies in dominance; the male oriented moral framework. Of the twelve chapters, female lives are particularly characterized. Their livelihood and lives; provide little light in the tough tunnel of existence. Deprivation and exploitation; from birth, through adolescence into adulthood and old age is common. Unheard echoes from a marginally discriminated population remain subject to communal dust.

There are two selections of the writings of Mahasweta Devia. In 'Notes on Contributors' assembled by Aruna Chakravarti; the author sketch informs us that "Her specialization lies in her studies of Adivasis, Dalits and other marginalized people of India...Her works have been widely translated and she has been the recipient of several prestigious awards in India...One of her novels was shortlisted for the Man Booker Award and she was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 2012." She was born in 1926 in Dhaka and passed away in Kolkata in 2016. Mahasweta Devia was not a member of the marginalized Dalit caste. I have selected 'The True Life Story of Uli-Buli's Mother' as presentation of the essence and depth of her writings and acute ability of the translator to convey the entirety of the text. Four other presentations highlighting a selective text follow.

"Uli-Buli were the twin girls she gave birth to. "Shame on you!" my husband used to say. 'First one girl, then another; and now two together! I"ll find myself another wife.' 'Do that, I would weep and plead. But don't drive me away. I'll move out of the house and live in the cowshed with the bull calf...I work in five houses even now, cleaning cowsheds and making dung cakes. I'll feed myself...I summoned up all my courage and approached the village elders. No land. No roof above my head.' I wept. 'Where will I live? I have four daughters." In response, Uli-Buli's father says: 'Why does she give birth to girls?...I've heard Dada say that she went prancing to the pond anytime she felt like it. She would eat mussel chachhari on Saturdays! Won't evil spirits enter such a woman's body and spoil her womb?"

"Twelve greybeards sat with long faces...The decision was reached that husbands would be found for the two older girls...One bridegroom needed a second wife and the other a third. Everything was sold. The house and land, the bull calf, my nose stud and ear-rings..." "I would beg during the day and sleep under the porch at night. And it was from there that my Uli and Buli were stolen..." The twins were a year old and sold to a hospital. Four years later, she comes to know of this happening and searches for her twin daughters for twenty-three years. "Her daughters would have been twenty-four years old today...wouldn't they?...She doesn't understand that. She searches her one-year olds. She thinks she will find them someday...She howls and beats her breasts. Swears and curses. Rushes at them. She looks the way she does but she's really quite young...Perhaps all women with a life story like Uli-Buli's mother look like her."

*A story to tell and tough to look away. Reviewer*

Another entry is 'Motho's Daughter' by Kalyani Thakur Charal. She was born in the Nadia district of West Bengal in 1965. Her family belongs to the Matua community. 'Notes on Contributors' inform us that "Her parents played an important role in her early upbringing by ensuring that she got an excellent education as well as instilling in her a pride in her womanhood... Today she is hailed as a prominent Dalit feminist writer of West Bengal." She has publications in poetry, short stories, essays and an autobiography. "She runs the Dalit women's magazine Neer and is on the board of a publishing house which focuses solely on Dalit writing. She lives in Kolkata."

"If you are poor the only one you can call out to, when in trouble, is God...' "Never forget Thakur's advice.' Starve if you have to. But don't neglect to give your children an education. That is His fervent wish.' "Nishikanta and his wife belong to a sect of Krishna worshippers who call themselves Motho...Mothos value learning above everything else...Bibhavati, too, is a passionate advocate of the cause."

"Nishikanta slaves from morning till night but takes care to wake up at dawn to feed the cow. Picking up the pieces of straw that have fallen from Bibhavati's bundle he goes to the cowshed and drops them in the feeding trough. Then, as one continues to boil the paddy the other tends to the cow...She does all this plus much more, day after day, month after month, year after year. Nishikanta toils in the fields...He cleans the cowshed, milks the cow and shakes it out to graze day after day, month after month, year after year...Is it to relieve the dreary monotony that husband and wife have turned to religion? Do they frequent Hari Shabhas and Mahotsavs to forget, if only for a little while, their lifeless, colourless, bleak, arid existence?...If so, where is the harm?...they convey their joys and sorrows to the Lord or seek his help with the family finances and the welfare of their children...there is nothing wrong with that surely?"

"Her younger son has failed her. He has given up studies and fallen into bad company...Worry eats her like a canker. She voices this fear wherever she goes. He is able to internalize sorrow and not show it...The boy comes home drunk every night...Bibhavati can't bear this blow to her hopes...She becomes so ill that no doctor can save her. "With Bibhavati's passing, Nishikanta's world crashed around him. The others had cleared their exams, found jobs and established themselves. The only one left at home was the problem son. Nishikanta decided to get him married...He found a girl from his own community. She had little education. Nishikanta was disappointed but how could he expect a better match for a worthless boy like his son? The daughter-in-law came and took charge of the house...She was a good girl. Pious and hardworking...Within a year she gave birth to a son, then another year...another. Nishikanta's house started bearing a festive look. But Nishikanta wasn't happy. Because the one thing she did not do was to teach her children the value of education and exhort them to study...Within a few years they followed in their father's footsteps and dropped out of school."

"And when Bibhavati's absence became unbearable...he beat his chest and shouted so loud...everyone could hear him. 'What have I done, O Thakur! What sort of Motho's daughter have I brought home as a bride for my son?

*One feels deep compassion for human aspirations whilst combating traumas. Reviewer.*

'Shonkhomala' is written by Manohar Mouli Biswas. "He was born into a Namashudra family in Khulna, now in Bangladesh in 1943. Navigating a challenging trajectory marked by poverty...he managed to overcome all the hurdles an unjust society placed in his path and attained an education. Today he enjoys the reputation of being one of the most prominent Dalit writers of West Bengal...and an autobiography titled 'Aamar Bhubane Aami Benche Achi'. 'He lives in Kolkata and works as a staunch advocate for Dalit causes in West Bengal."

"All his life Manush Dom had fought against overwhelming odds...Why his parents had named him Manush (Man) he did not know. For, though human, he had to endure dishonour and humiliation every day. He had been treated like an animal...A daughter of surpassing beauty had been born to him. And out of a great flow of filial love, Manush had named her Shonkhomala...a garland of conch shells...How this gleaming beauty metamorphosed into an evil spirit lurking in the dark shadows of a bamboo clump, is what this story is all about."

"As Shonkhomala grew to be a woman...She was gorgeous of course, no one could deny that, and her voluptuous body was meant to be enjoyed. But only in secrecy...She was a dom's daughter, after all, and marrying her was out of the question...Who will dare to make a dent in the iron-bound structure set up by the Vedas three thousand years ago? The tradition of caste apartheid flourishes, to this day, in full and pompous glory. Marriage outside one's cast is deemed to be worse than death...The surname Dom is obnoxious. To hear it is to feel aversion and contempt. Upper-caste folk abhor the caste so much, they are afraid to step into a dom's shadow...But things have started to change. Doms have begun questioning the wisdom of proclaiming their caste through their names. Why should we wear the badge of shame, thrust upon us by a cruel social order, on our sleeves?"

"Though she hasn't received much education, she has only cleared School Final Exams, she has a fund of natural intelligence." Her husband Harikanta was illiterate. "At the party office which he visited from time to time...it was difficult to survive in the village if one didn't do some work for the party...Your name is on record in the official documents, the party babus told him. 'You belong to the Scheduled Caste. Why do you or any of your caste need an education?'...Harikanta wasn't a poor man. He was the owner of three-and-half acres of land and one acre of forest in which bamboo and cane grew in profusion...He had two sons and two daughters. The village school was not a good one....What little the children had learned had been through efforts and that of their mother....Mother and daughters worked hard all day and father and sons took their produce ... to sell at the weekly haat. There was no lack of food or, indeed, any other kind of deprivation in Shonkhomala's household.""

"The babus had informed him that the Tatas were building a motor car factory and were taking possession of land." Since his land fell within the area, he had to sign a form giving permission. "Illiterate as he was, he had signed the form without knowing what he was doing." His family "cried out in shock. "No. Never. We won't give up our land. Why should we? ...It sustains us all year round. What use will a motor car factory be to us?...The party babus said that once the factory is built, Singur will become a flourishing town....He simply parroted what the babus have said to him...Dismissing her husband's explanations with an impatient wave of her hand, she stood up. 'Go get all our neighbours together' she commanded her children...We must have a meeting...All those who were against giving up their land were there...Shonkhomala opened the meeting...a motor car factory, in place of the good arable land our ancestors have farmed for generations, will be of no use to us. Our boys have little education. What work will they do in the factory? The babus are aiding and abetting the Tatas to benefit their own sons. Many of them hold engineering degrees but have remained unemployed for years. The factory will come in useful for them. Why should we give up our land for their welfare?...There was a roar of applause from the people present...It was decided that a great procession, opposing the move, would be taken out the next day."

"At early dawn a band of goons barged into Harikanta's house and carried off Shonkhomala. She was gang-raped in her own bamboo grove and murdered. Pouring petrol over her dead body they burned it to ashes...Harikanta and his children have left the village. As for Shonikhomala, she has turned into an evil spirit whom everyone fears. No one dares walk through the bamboo grove which she guards with all the power of her metamorphosed state."

*Her defiance results in self-destruction. The deserted jungle continuously echoes her presence. Reviewer.*

To be continued...

Raana Haider has an MA. in Sociology from the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. She has taught 'Women and Development' at the Cairo Center for Development. Her publications in the have been on Environment and Gender issues; publishers being The American University in Cairo Press and The University Press Limited (UPL), Dhaka. She resides in Dhaka.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Pedaling Through the Mangroves ...

The journey from the bustling streets of Barishal to the serene, emera ...

Why the Interim Government mus ...

Two weeks out from what is expected to be a red letter day in the figh ...

Doesn’t matter who thinks what about Bangladesh deci ..

The Other Lenin

US President Donald Trump said his administration

Govt moves to merge BIDA, BEZA, BEPZA, MIDA