Essays

2nd Edition (Digital), Published by Portraits (2025)

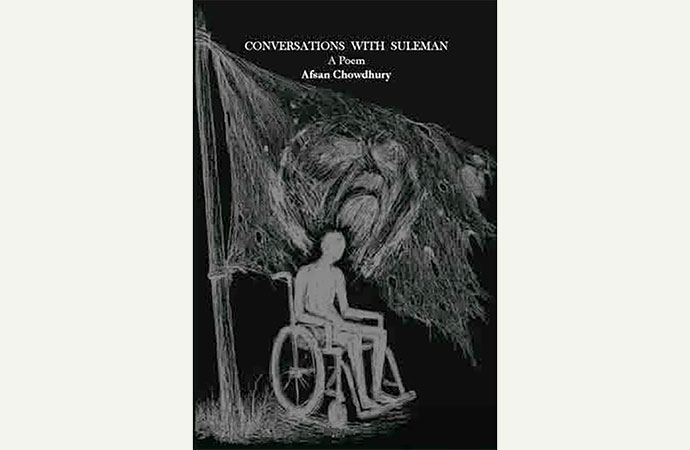

The poem arrives as a fragmented field report from a paralysed man's wounded history. Suleman's memory enters without a knock, speech breaks into convulsions as the poet seems to write from the nerve of war and its long afterlife. What reveals is not really a retelling of 1971, but a reckoning; private, unruly, and strangely choral.

The poet, Afsan Chowdhury, I think, had little control over his work. The narration took over, speaking in its own fever, dragging both the poet and the reader into its ward. There is something feral about Suleman's relentless continuation. The voice becomes plural, contradictory, delirious. The rhythm stumbles and gasps. One can hear and smell the city through it, its rains, drains, cigarettes, disinfectant, fireworks, fools, madmen, stragglers, and their amputated dreams.

"What shall I do with these hands?" mutates into "No hands...no hands...no hands..." and perhaps into something even larger, larger than lament: what to do with history, with belief, with the unfinished body of a land. Hands that once dug and shot, now tremble over a keyboard; what once promised freedom has settled into the stasis of wheelchairs. "These hands," sometimes they pray, sometimes they curse, and somewhere in between, the war keeps returning, less as an event and more as a nervous system of this paralysed man. And perhaps this is where Suleman exits the book as his hands re-form to shake hands with the poet's other compadres: the dead poets, Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Eliot, and more.

It is almost impossible not to sense their ghosts murmuring to the poet's sensibility. With its allusion to Macbeth, "In thunder, lightning, or in rain/ when shall we meet again?" the poem extends its own boundary and, in a Baudelairean way, "You hypocrite reader, my brother, my double!" reminding readers that they are never outsiders to literature or what they confront, and that literature, perhaps at another height, offers a handkerchief to its tormented, agitated reader. So says Suleman, "...you, who come to watch and weep and despair."

These are not merely influences, I would say, but echoes, the way certain shadows fall across language when it begins to shake.

After all, what stays is neither the war nor Suleman, but the exhaustion of memory. The poem becomes a mirror held too close, in which the poet, the fighter, the cripple, the bureaucrat, blink in the same dim light. Once felt, it is revealed as a human condition: the slow corrosion of faith, the body turning into a document of history. "Suleman battles on, therefore I am," and it is no metaphor. Survival itself has become the poem's final act of faith.

The poem is difficult, but what is poetry but a safe space for difficult truths?

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Remembering Kalidas Karmakar ( ...

The art world remembers Kalidas Karmakar, a visionary whose creativity ...

An Evening with Shishir Bhatta ...

Cosmos Art Echo, the artist talk initiative of Gallery Cosmos and Cosm ...

Myanmar denies genocide, calls Rohingya crackdown co ..

Yes, of course

Earth’s average temperature last year hovered among ..

Bangladesh and Singapore: A Tale of Two Nations