Essays

How Enayetullah Khan Reimagined the Bangladesh-Singapore Story

It rarely happens that a book launch becomes a metaphor for the story it seeks to tell. But when Bangladesh and Singapore: A Tale of Two Nations was unveiled aboard a vessel floating across Singapore's waters, the symbolism was impossible to miss. Seas have long connected these two Asian nations; history, commerce and culture have travelled the monsoon winds between them for centuries.

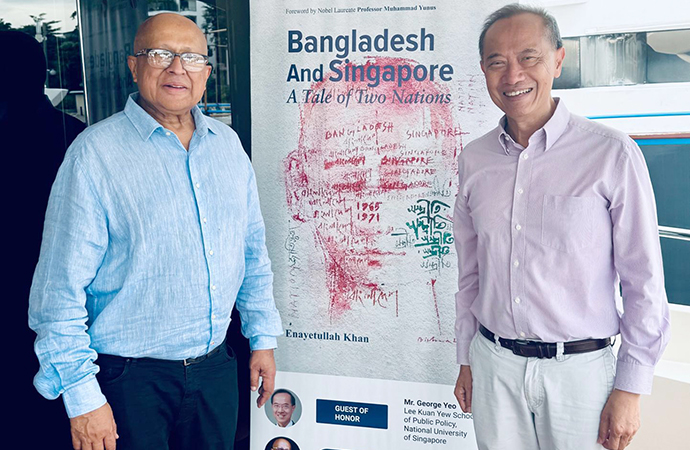

The book, written by Bangladeshi entrepreneur, conservationist and publisher Enayetullah Khan, explores precisely this deep and dynamic relationship. And its launch - attended by former Singapore Foreign Minister George Yeo Yong-Boon, scholars and friends - was as suggestive as the narrative itself.

Yeo, invited as Guest of Honour, set the tone with a speech that was at once humorous, reflective and, in parts, profoundly personal. He began seated, invoking an old naval tradition learned during his days at Cambridge: the privilege of remaining seated while speaking, a courtesy extended to naval officers. "If I stand up, I will feel a little woozy," he laughed, before steering the audience into a sweeping meditation on the monsoon-bound histories of Bengal and Southeast Asia.

A Shared History Written by Monsoons

Yeo's argument was simple yet arresting: geography begets history. Bangladesh's great rivers - the Indus, Jamuna and Brahmaputra - empty into a delta that has for millennia nourished people, ideas and commerce. "A land is so fertile that if you have a stick and you put it in the ground, it will grow." From there, the monsoon currents carry ships, pilgrims and traders towards Southeast Asia, rounding Singapore as if by natural design.

These currents were also cultural highways. Yeo traced the maritime spread of Buddhism to the seas connecting Bengal and Southeast Asia. He recalled the extraordinary journey of Atish Dipankar, the Bengali monk who was born in what is today Bangladesh, trained at Nalanda, refined (Is ths he right word?) in Sumatra, and who was later revered in Tibet and the Himalayan world. Yeo visited his birthplace during a trip to Bangladesh years earlier and found it "a sorry sight" - a modest stupa atop relics gifted decades ago by Zhou Enlai. For him, the site symbolised both the ancientness of Bengal and the fragility of its memory.

Similarly, he invoked Tagore's journey through Singapore, his dream of creating a "China House," and the role of Tan Yin Shan, the Chinese teacher whomTagore recruited on a stopover. He reminded the audience that Subhas Chandra Bose established the Indian National Army in Singapore, drawing soldiers away from the British to fight for India's independence. The British destroyed the INA memorial; Nehru later came to lay flowers on its rubble. Such stories, Yeo suggested, illustrate the deep and layered connections between Bengal and Singapore, forged long before the modern states existed.

Against the Headlines: A More Nuanced Bangladesh

Yeo's reflections turned repeatedly to a point he felt strongly about: Bangladesh is too often judged by "the headlines" - by political strife, personal rivalries and moments of cruelty. Yet beneath these surface tensions, he insisted, lies a country whose social indicators and human resilience astonish.

He recalled argumentative sessions with Amartya Sen during the revival of Nalanda University. Sen, whose father taught at Dhaka University, once told him: "The country is doing well, despite thepoverty." Bangladesh, he said, had overtaken not only India but also West Bengal on key social indicators - a point that startled many in the room.

For Yeo, the strength of Bangladesh lies above all in its women. Microfinance, pioneered by Grameen Bank, succeeded because "the womenfolk were never before on the loan (Do you mean "default"?) because their lives depended on it." Their drive, discipline and determination built the foundation of a transformative economic story.

Enayetullah Khan: A Man of Two Nations

If Yeo spoke of ancient winds and forgotten histories, Enayetullah Khan's remarks brought the focus to the present - and the future. Introducing himself as "a man of two nations," he said the cruiser was a fitting venue: "A yacht floats on the seas, and seas move between nations."

His book, he added, is both a personal and an intellectual journey across these waters.

Khan's vantage point is unusual but compelling. Having visited Singapore since the 1970s and now dividing his time between the two countries, he possesses an instinctively comparative view of their trajectories. His "ecumenical" approach - embracing politics, economics, culture, history and regional strategy - gives the book its distinctive flavour.

He outlined the themes of the work: the parallel struggles for decolonisation; the resonances of nationalism in two young nations; the founding roles of Lee Kuan Yew and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman; and two institutions whose innovations altered economic history: Singapore's Housing and Development Board and Bangladesh's Grameen Bank. These institutions, he argued, anchored each country "in economic time."

Economics, for Khan, is inseparable from "social and political negotiation." Rather than indulge in the simplistic trope of "if Singapore could do it, so can Bangladesh," he stresses that each nation's choices arose from their own political bargains. Yet, he maintains, they can still learn from one another in meaningful ways.

The Bay of Bengal: A Region Waiting to Awaken

A major thrust of Khan's book - and his speech - is the case for reimagining the Bay of Bengal. The world's largest bay, bordered by five countries including Bangladesh and India, should by all logic be a vibrant economic zone. Instead, intra-Bay trade hovers at just over 6 per cent - dwarfed by ASEAN's 23 per cent.

But change is coming. Deep-water ports, power grids and infrastructure projects, such as Matarbari in Bangladesh and Colombo's vast expansion, signal a region beginning to reconnect. Behind this momentum lies a mix of opportunity and strategic anxiety, including efforts to balance China's Belt and Road Initiative.

Khan urged the audience to "look at the Bay of Bengal with new eyes," noting that it has become a critical theatre in the Indo-Pacific, a concept sharpened by the United States to frame its competition with China. Within this reshaped geopolitical map, Bangladesh and Singapore are "nodal nations": small in power terms but skilled at navigating great-power politics.

Small States, Big Stakes

Both speakers dwelt on a shared theme: small states survive not by retreating but by mastering the art of strategic leverage. For Yeo, this meant understanding the Darwinian logic of global politics, where "the strong do what they will and the weak do what they must." Small nations, he argued, survive by "borrowing power", that is, by aligning, negotiating and manoeuvring with agility. For Khan, an eventual Free-Trade Agreement between Bangladesh and Singapore would be more than an economic pact. It would signal a shared faith in interdependence, a belief that cooperation can absorb shocks and reconcile differences. FTAs, he said, are "strategic instruments."

A Relationship Rooted in People

Beyond strategy and history, both men recognised that the Bangladesh-Singapore story is also a human one. Singapore is home to a large Bangladeshi community - workers, professionals, entrepreneurs - who build, clean, innovate and contribute to the city-state's daily life. For many Bengalis, Singapore has become "a home away from home."

This people-to-people dimension, Yeo said, is what gives the relationship depth. Small and medium enterprises in Singapore have long seen opportunity in Bangladesh, long before the headlines acknowledged the country's economic rise. The ties are real, lived and constantly renewed.

A Tale Still Being Written

In the end, the launch felt less like a formal occasion and more like the continuation of a familiar conversation, one that has drifted through centuries with monks, traders, sailors and wandering dreamers. Khan's book, woven from research as well as memory, joins that old exchange. Yeo's remarks, filled with small historical detours and an easy humour, felt like a blessing the moment deserved.

As the yacht eased its way across the water, the two countries - one shaped by the fires of 1971, the other by an astonishing sprint of development -seemed less like opposites and more like natural companions. Bound by the monsoon, marked by migration, and tied to the sea, Bangladesh and Singapore appeared, just as the book argues, to be two stories growing towards each other.

If the hopes voiced on that deck take root - a stronger partnership, a refreshed vision of the Bay of Bengal, even future FTAs - then this chapter is hardly an ending. It may only be the first few lines of a story still finding its way forward.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Populism strikes again

So it is official now - the Bangladesh national team will not be trave ...

Beijing urges Washington to fo ...

China on Thursday reacted to China-related remarks by the US Ambassado ...

The European Union and the Mercosur bloc of South Am ..

New US Ambassador to Bangladesh raises concern over ..

Gold prices in Bangladesh surged past the Tk 250,000 ..

What is Trump's 'Board of Peace' and who will govern ..