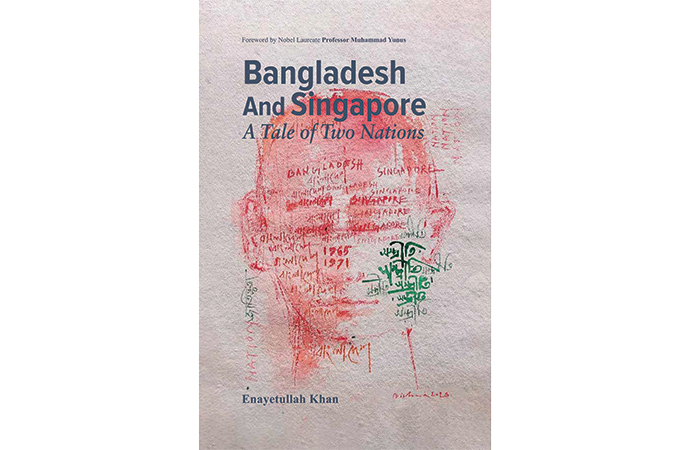

Essays

By Enayetullah Khan, Cosmos Books, 2024, 236 PAGES, BDT 1,000.

There are roughly three popular Bangladeshi views of Singapore. The first is that of the thousands of Bangladeshi migrant workers who throng to the city-state to make a living. Their view is extremely important because their labour contributes to the economies of both nations tangibly. The second view is that of Bangladeshi professionals who live and work in Singapore. Their intellectual view seeks to balance Singapore's sterling economic performance against its early political record as an authoritarian state. The third, internationalist, view emphasises bilateral ties between two essentially small states against the backdrop of great-power competition and rivalry. Economic imperatives form a firm part of this internationalist view.

In this book, Enayetullah Khan offers a fourth view that goes beyond these approaches. His perspective emanates from him being an entrepreneur (who has built the Cosmos Group into a globalised Bangladeshi conglomerate); a nature, heritage and ocean conservationist; a patron of the arts; and a champion of media freedom. Having visited Singapore regularly since the 1970s, he has been privy to an organically comparative view of the progress of two states whose birth was separated by just a few years. (Singapore was born in 1965.) Now, he divides his time between Bangladesh and Singapore, thus keeping abreast of developments in both countries.

Khan's many personal facets are reflected in what I can only call an ecumenical view of the two countries. He covers an exhaustive range of issues: the trials of decolonisation that led to the births of the two nations; the role of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in connecting anti-colonial Bengal and Japanese-ruled Singapore; the comparable characteristics of nationalism in the two countries; and the role their founding fathers, that mantle falling on Lee Kuan Yew in the case of Singapore. There is a reflective chapter on two institutions - Bangladesh's Grameen Bank and Singapore's Housing and Development Board - that have anchored each country's place in economic time. A passionately argued chapter focuses on the role of culture as an underwriting institution in national development. The chapter on economics reveals, with consistent intellectual lucidity, how Bangladesh and Singapore chose the economic paths that they did. Mercifully, there is none of the nonsense about "see, if Singapore could do it, so can Bangladesh" - a trope familiar in post-colonial panegyrics to success. Khan's own profound understanding of economics as a function of social and political negotiation leads him to mention the strengths of both countries and to suggest how they could learn from each other. Finally, he places Bangladesh and Singapore in their regions - South Asia and Southeast Asia - to show how these two countries have made, and could continue to make, a crucial difference to their regions' interplay with the great powers.

This last dimension bears dwelling on. Both Bangladesh and Singapore have proved that it is possible for small powers to survive without becoming captive to the designs of regional powers. Singapore has done so by pursuing an adroit balance-of-power policy in which it has drawn in the countervailing influence of the United States to counter the constrainment of Singapore's sovereign freedom of action. Singapore's true success lies in the way in which it has made America a durable security partner without having antagonised Indonesia and Vietnam, the chief regional powers of Southeast Asia. However, as the geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China (and Russia) grows, Singapore's ability to have good relations with both sides will be tested because each side will seek to pull strategically important Singapore into its exclusive sphere.

So it is for Bangladesh. Its foreign policy will be tested by the increasing pace of Sino-US rivalry, one in which India, the largest South Asian power, has been drawn in already on the side of America. Bangladesh's difficult relations with India at the moment should not obscure the need for Bangladesh to fit into the emerging pattern of great-power relations in South Asia.

This, to me, is the final lesson of this book. Great powers live by strength, small powers by their wits.

Having come so far, Bangladesh and Singapore owe it to themselves to preserve the fruits of their hard-won independence.

Mahfuzur Rahman, Editor, United News of Bangladesh (UNB).

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

A total of 2,582 candidates su ...

A total of 2,582 candidates submitted nomination papers to contest the ...

A fitting farewell for a giant

The nation has said goodbye to Begum Khaleda Zia, one of the undoubted ...

A Kenyan barber who wields a sharpened shovel thrive ..

A rough year for journalists in 2025, with a little ..

The West Is Not Ready for a Multipolar World

Silicon Valley Socialism