Column

Testimony of Enforced Disappearances and the Resistance of Memory, a recent event in Dhaka (Photo: Prothom Alo)

Recently, Begum Khaleda Zia attended the Armed Forces Day ceremony at the Army Headquarters in Dhaka, where she posed for photos with Professor Yunus and key student leaders of the interim government. The image of these political figures, including military leaders exchanging pleasantries with Zia, struck me as a potential blueprint for Bangladesh's future.

At the heart of Bangladesh's political landscape today are three forces: Professor Yunus, student leaders, and the military. Together, they represent the architects of a new Bangladesh, while figures like Begum Zia and her party wait on the sidelines to claim ownership. Though these players are rivals, they need each other to move forward. The interim government cannot function without political party support, and those seeking power must wait for promised reforms and elections to be fulfilled.

This photo gives me hope. Despite fierce political competition, Bangladesh's key leaders have shown they can work together. This civility, absent for the last fifteen years, suggests that, even in opposition, mutual cooperation is still possible.

But can this cooperation extend further? Can we envision including the Awami League, the largest political party in the country, in this dialogue? I'm not referring to the past authoritarian regime and its defenders, but rather to the broader base of the Awami League, which, despite its oligarchic past, still includes many ordinary members and supporters who've suffered under the same system.

The authoritarian rule of the past fifteen years has deeply divided Bangladesh. Political rivalry has bred hatred and suspicion, even to the point of refusing to engage with anyone outside one's own party or ideology. This "tribal mentality" has become the norm. It's a legacy of authoritarianism that must be undone if the country is to heal.

Bangladesh is not alone in this. Nations like Colombia, Bosnia, Rwanda, and Sri Lanka have all experienced deep political and ethnic divides, but over time, many have sought paths to reconciliation. In these countries, even after violent conflicts and civil wars, communities have found ways to coexist peacefully, despite their pasts. The key to this reconciliation is a shared agreement among citizens and leaders that peaceful coexistence is not only possible but essential.

Reconciliation begins when communities acknowledge that their differences are secondary to the need to live together as citizens of the same nation. This requires not only political will but active citizen participation. Without both, reconciliation cannot succeed.

We've seen this process work in countries like South Africa, Northern Ireland, and Rwanda, where political leaders and citizens came together to move beyond the past. In Rwanda, after the genocide of 1994, the Gacaca courts allowed perpetrators to face victims in public, acknowledge their crimes, and seek forgiveness. Some perpetrators received punishment and the victims were awarded symbolic monetary compensation. This process allowed the country to begin healing and restoring a sense of unity, despite the horrific past.

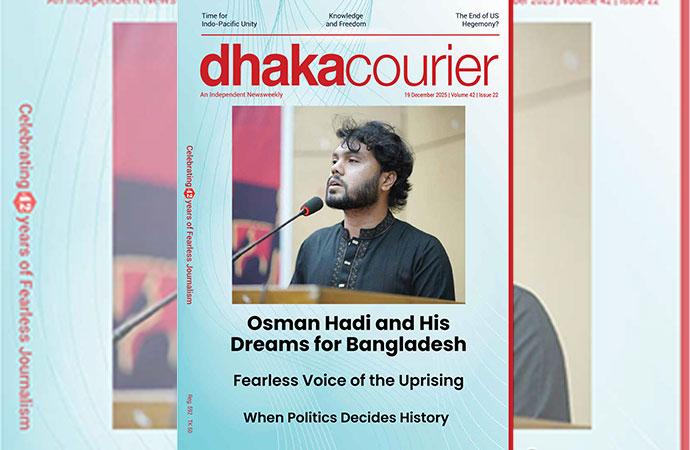

Can we consider a similar model for Bangladesh? While we don't have Gacaca courts, an initiative called "Testimony of Enforced Disappearances and the Resistance of Memory" was held in Dhaka, where victims of the past regime shared their stories. Though the accused were not present, the event allowed the voices of the oppressed to be heard, which could be a starting point for a larger national reckoning.

Such events, if broadcast nationally, could serve as a public hearing on past crimes. Even without legal justice, it would offer victims a chance to be heard, a crucial step toward healing. Similar events could be held across the country, creating a public acknowledgment of suffering that might lighten the burden on the victims.

This could be a first step in a broader reconciliation process-one that doesn't seek to deliver immediate justice but aims to begin the healing of a fractured society. If the perpetrators could publicly admit their wrongs and victims could receive some form of compensation, it could serve as a symbol of our collective responsibility to heal.

A fund could be established, funded by confiscating the ill-gotten wealth of those who benefited from the past regime, to provide financial compensation to the victims. While no amount can replace a lost family member, it would serve as a gesture of national gratitude and acknowledgment of their suffering.

The question is whether Bangladesh's political leaders and citizens are ready to take this first step toward reconciliation. If they are, we may yet build a future where even the most bitter political rivals can find a way to coexist peacefully.

The writer is a journalist and author based in New York.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Pedaling Through the Mangroves ...

The journey from the bustling streets of Barishal to the serene, emera ...

Why the Interim Government mus ...

Two weeks out from what is expected to be a red letter day in the figh ...

Doesn’t matter who thinks what about Bangladesh deci ..

The Other Lenin

US President Donald Trump said his administration

Govt moves to merge BIDA, BEZA, BEPZA, MIDA