Reportage

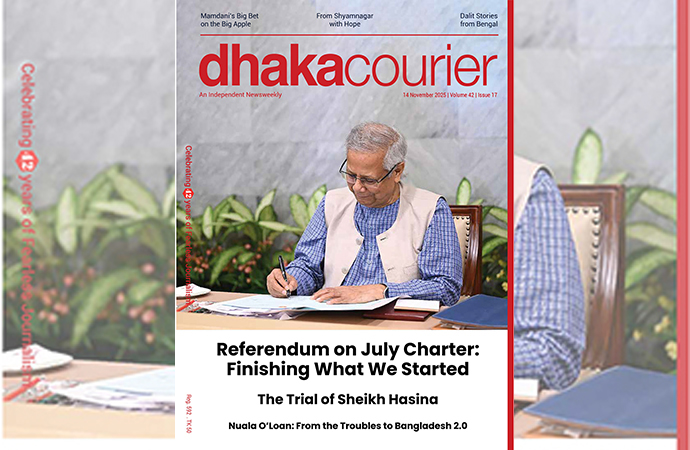

Constitutional Reform Commission members along with Chief Adviser of the Interim Government, Professor Muhammad Yunus. Photo: PID

The interim government formed a 7-member Constitutional Reform Commission on October 7, 2024, led by Professor Ali Riaz, to review and evaluate the existing constitution of Bangladesh and to recommend necessary amendments. This commission submitted its recommendations to the Chief Advisor, Professor Muhammad Yunus, on January 15, 2025. The full report of the recommendations made by the Constitutional Reform Commission was made public on February 8, 2025. Upon reviewing this report, it was observed that the Commission has recommended extensive and fundamental changes to the existing constitution, including its preamble and basic principles. Notably, the Commission has suggested removing secularism from the constitution while simultaneously proposing to retain Islam as the State religion.

Although these recommendations are currently only proposals, these will be finalized based on discussions with political parties and national consensus. Nevertheless, these recommendations will serve as the main foundation for dialogue and in building consensus. Therefore, it is necessary to review and analyze these recommendations. I will limit my discussion on the recommendation on amending the Constitution's preamble, where a clear proposal has been made to redefine the fundamental goals and objectives of the Constitution.

Recommendations on the Constitution's Preamble

The Reform Commission has recommended replacing the existing constitutional preamble with a new five-paragraph preamble. The new preamble omits the Proclamation of Independence of 1971, introduces significant changes to the principles, goals, and objectives of governance, and excludes the drafting, adoption, proclamation, and date of adoption of the Constitution by the Constituent Assembly in 1972.

The preamble is an integral part of the Constitution, enshrining its fundamental goals, objectives, and principles, while guiding the main Constitution. The removal of the Proclamation of Independence from the preamble has profound political, social, and cultural implications. The Proclamation of Independence is a historic document of Bangladesh's independence and liberation war. Through this document, on March 26, 1971, Bangladesh's independence and sovereignty were formally declared from Pakistan, and it served as the governing framework for the country from March 26, 1971, until December 16, 1972, when the Constitution came into effect.

The Proclamation of Independence reflects the aspirations of the then 75 million people of Bangladesh and was approved by the government formed by their elected representatives. Hence, it is a historic document, inseparably linked to the birth of the Bangladeshi state. Removing the Proclamation of Independence from the Constitution is akin to removing the birth certificate of Bangladesh.

Changes to the Fundamental Principles of the Constitution

The Reform Commission has proposed extensive changes to the fundamental principles, goals, objectives, and the preamble of the Constitution. Among the four existing fundamental principles of state governance-democracy, nationalism, secularism, and socialism (i.e., economic and social justice)-the commission has recommended excluding the latter three, retaining only democracy. In their place, the commission proposes incorporating equality, human dignity, social justice, and pluralism as the fundamental principles of the Constitution.

Now, let us examine the significance of these sweeping changes to the state's fundamental principles.

Secularism and Its Relevance

Secularism means that the State does not give special status to any religion, and State laws and policies are not based on religious principles. Secularism is intrinsically linked to the spirit of Bangladesh's Liberation War and independence struggle. The Constitution of Bangladesh in 1972 included secularism as one of its fundamental principles. However, during military rule in 1977, secularism was removed and replaced with "absolute trust and faith in the Almighty Allah." In 1988, Islam was recognized as the State religion. Later, in 2011, the principle of secularism was reinstated in the constitution, although Islam remained the State religion.

The State of Pakistan was created based on the two-nation theory-a separate State for the Muslim population. The communal nature of the Pakistani State and its discriminatory behavior towards religious minorities angered the majority population of East Pakistan. During the 1971 Liberation War, people of all religions, castes, and groups fought together against the Pakistani occupation forces with the aim of establishing a non-communal and inclusive State and society. Therefore, removing secularism means abandoning the spirit of the Liberation War. Furthermore, one of the State's primary responsibilities is to protect the rights of religious minorities. Secularism in the constitution acts as a legal safeguard for religious minorities. Many countries' constitutions provide legal protection for religious minorities; even our neighboring countries, India and Nepal, have such legal protections in their constitutions. Removing secularism would destroy the fundamental structure of the constitution.

Pre-Constitutional Concept of Secularism

The weak argument for removing secularism is that there was no mention of secularism in any pre-constitutional documents, such as the 1970 Legal Framework Order, the 1970 election manifesto of the Awami League, or the draft constitution of Pakistan proposed by the Awami League in 1971. Any mass uprising or revolution is a dynamic process through which people's thoughts, consciousness, and aspirations evolve. A bloody revolution like the Liberation War brought people of all religions and castes together and fostered their consciousness, as clearly stated in Professor Rehman Sobhan's speech. According to Prof. Sobhan, after the 1969 mass uprising, the demands for regional autonomy, democracy, social justice, and secularism in East Pakistan were united in a broader movement. This statement by Prof. Sobhan is supported by Prof. Ali Riaz's Ph.D. research. In his research book published in 1993 by the University of Hawaii, Prof. Riaz mentions that, consistent with the spirit of the independence struggle, the Awami League proclaimed the high ideals of nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism as fundamental principles in the constitution.

As a result, secularism became an integral part of the spirit of the Liberation War. Prof. Asif Nazrul mentions in several of his speeches that there were extensive discussions on secularism in the Constituent Assembly, and the most vigorous arguments in favor of secularism were made by Khandaker Mushtaque Ahmed, a leader of the right-wing faction of the Awami League.

Pre-Independence Concept of Secularism

In fact, right after the creation of the State of Pakistan, in 1950, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani demanded secularism. During the movement of 1950, he raised two demands: one was the right of self-determination for the Bengali nation, and the other was secularism-keeping the State separate from religion. This was reflected in the removal of the word "Muslim" from the Awami Muslim League's name in 1955. The concept of secularism existed in Bangladesh even before the creation of Pakistan. Sher-e-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Huq said at the All India Muslim League Conference in 1918 that there was no difference in the exploitation and oppression by Hindu landlords and Muslim landlords, Hindu moneylenders and Muslim moneylenders. All poor farmers, regardless of being Hindu or Muslim, were similarly victims of exploitation and oppression. Therefore, the issue of exploitation of Muslim farmers was not communal; at its root were the zamindari (landlord) and mahajani (moneylender) systems. Hence, both Hindu and Muslim communities should reject communalism and work towards abolishing the zamindari and mahajani systems.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, realized the importance of secularism immediately after the creation of Pakistan. In the first session of the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, he firmly stated that Pakistan would be a State where every citizen, irrespective of religion or caste, would enjoy equal rights and freedom. He clearly declared, "You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques, or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste-it is no concern of the State." State decisions would be made on political grounds, not religious ones. However, after Jinnah's death, the then leaders of Pakistan deviated from his ideals and integrated religion into State governance.

Pluralism and Secularism

Another argument for removing secularism as a fundamental principle of the State is that "secularism is not consistent with the concept of a pluralistic society in Bangladesh and is essentially anti-democratic." Pluralism is a modern concept that is relatively new to the culture and politics of Bangladesh, and its essence is still not understood by many. However, secularism and pluralism are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary. Secularism ensures the freedom for followers of all religions to practice their respective faiths freely, which in turn supports the coexistence of all religious believers and aids pluralism. In many countries such as Canada, France, and the United States, secularism and democracy coexist. Furthermore, secularism is a fundamental human right, while pluralism is an ideal, a desired goal. We certainly aspire to achieve pluralism, but not at the cost of fundamental human rights like religious freedom.

Self-Contradiction in the Argument for Removing Secularism

One of the major self-contradictions in this report is that it recommends removing secularism on one hand, while on the other hand, it suggests retaining the current constitutional provision of the State religion, i.e., Islam. It also recommends including "Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim / In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful" in the preamble of the constitution. They propose removing secularism under the guise of pluralism, while simultaneously recommending a State religion, which contradicts the Commission's stated principles of pluralism and equality and goes against democratic values. Notably, Prof. Riaz, in his book on the political history of Bangladesh, described the inclusion of "Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim" in the constitution through the Fifth Amendment in 1977 as 'Islamization of the constitution and the State' and described it as a severe blow to secular politics in Bangladesh and a pathway for the rise of religious forces in politics.

Prof. Riaz was a staunch critic of the Eighth Amendment to the constitution during H. M. Ershad's regime, which declared Islam as the State religion. Naturally, the question arises as to why there is such self-contradiction in the Reform Commission's recommendations on secularism. From the above discussion, it is clear that the arguments for removing secularism from the constitution are extremely weak, self-contradictory, and contrary to the spirit of the anti-discrimination student movement and the July 2024 mass uprising. Just like the Liberation War, the July 2024 mass uprising also saw people of various religions and beliefs unite against the autocratic government with the goal of establishing a non-discriminatory State. The introduction of Islam as the State religion has profoundly affected the character of Bangladesh's constitution and created a division between Muslim and non-Muslim citizens in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is a multi-religious country, where, besides Muslims, the Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, and indigenous communities reside. The recommendation to remove secularism from the constitution could increase divisions society, weakening national unity and negatively affecting social harmony.

Nationalism and Constitutional Principles

Let us now turn our attention to another fundamental principle of the Constitution - nationalism. While there are many arguments both in favor of and against nationalism-since nationalism can sometimes inspire extreme or narrow ideologies-it also has many positive aspects. Nationalism is a symbol of national unity, solidarity, and identity.

In Bangladesh, two streams of nationalism flow concurrently. The first is Bengali nationalism, rooted in the Language Movement of 1952, the movement for autonomy in 1966, the mass uprising of 1969, and the Liberation War of 1971. Its roots lie in language, literature, art, culture, and traditions. The second is Bangladeshi nationalism, which is based on the collective identity and rights of all ethnic groups within the geographic boundaries of post-independence Bangladesh.

Despite the differences between these two streams, they converge on one key point-patriotism, a sense of national identity, and self-recognition. Both aim to unify the people of the country, inspire patriotism, and strengthen their sense of identity.

Therefore, for a young nation like Bangladesh, the ideals of nationalism-patriotism and self-identity-are of utmost importance. In this context, it is worth considering how appropriate it would be to remove "nationalism" as a fundamental principle of the Constitution.

Dropping the Final Paragraph of the Preamble

The Reform Commission has suggested modifications to the concluding paragraph of the current constitutional preamble, excluding essential details including the adoption process, the authority responsible for adoption, and the adoption date. Instead, the recommendation states: "With the consent of the people, we adopt this Constitution as the Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh."

This implies that the commission is proposing the replacement of the 1972 Constitution with a new one. Such a recommendation raises numerous fundamental questions, including: How was the "consent of the people" obtained? Who are referred to as "we"? What is the source of their authority to adopt a constitution? Who drafted this constitution, and what authority did they have? And on what date was this constitution adopted?

This fundamental change to the preamble could plunge the country into chaos and a serious constitutional crisis.

The Reform Commission's Jurisdiction

The key question is whether the commission has the authority to draft or adopt a new constitution. The gazette notification issued by the interim government on October 7 explicitly defines its mandate. It states that the Constitutional Reform Commission was established to "review and evaluate the existing Constitution and prepare a report with necessary recommendations for its reform."

The government's directive makes it clear that the commission's mandate was to propose necessary reforms to the existing Constitution-not to discard it or draft and adopt a new one. By recommending changes to the final paragraph of the preamble, the commission has overstepped its jurisdiction. As the preamble defines the fundamental characteristics of the Constitution, the commission lacks the authority to alter it.

Proposed Fundamental Principles

Now, let us examine the fundamental principles proposed by the commission. The revised preamble suggests "equality, human dignity, social justice, pluralism, and democracy" as the Constitution's core principles. However, their meanings remain unclear, as these broad concepts are open to multiple interpretations. For instance, "equality" can span social, cultural, political, and economic dimensions, including equality among different classes and professions, gender equality, and equality among ethnic groups.

There is little debate about the importance of "human dignity" and "pluralism." Additionally, the Proclamation of Independence of 1971 emphasized equality, human dignity, and social justice. However, these concepts serve as societal goals and objectives-milestones toward which the nation aspires to progress gradually and systematically. They do not, however, constitute the fundamental principles of state governance.

The distinction lies in the fact that a state's goals and objectives are not the same as its fundamental principles of governance. The fundamental principles of the Constitution are the core values that guide the state's functioning and represent the nation's ideals. In contrast, the goals and objectives of the state are the milestones it seeks to achieve in the future.

Debate on Pluralism as a Core Constitutional Principle

Pluralism is a valuable modern concept that promotes the coexistence of diverse religions, races, opinions, lifestyles, and ideologies. However, is our society ready to embrace it? For example, in many parts of the world, cohabitation of unmarried couples is considered normal, and homosexuality is accepted in some countries. But is our society prepared to accept these practices? Probably not.

While the goals and objectives of our Constitution may be broad and ambitious, the fundamental principles of state governance must align with the existing norms and values of society. Although pluralism is an ideal principle, its adoption as a core constitutional principle may lack sufficient societal precedent.

The Basic Structure Doctrine of the Constitution

The Constitution is the supreme law of the state, embodying certain fundamental characteristics and features. The Basic Structure Doctrine defines the process and limitations of constitutional amendments, asserting that no reform or amendment can alter the essential features or core principles of the Constitution.

Although the legislature has the authority to amend the Constitution, this power is not absolute. It cannot enact changes that undermine the Constitution's fundamental characteristics. The Basic Structure Doctrine acts as a safeguard, with the Supreme Court serving as its protector, ensuring that the Constitution's core principles remain intact.

Sovereignty, democracy, the rule of law, and the fundamental rights of citizens are considered essential components of the Constitution's structure. This principle was first established in India through the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case of 1973 and later incorporated in Bangladesh in the Eighth Amendment Case (Anwar Hossain Chowdhury v. Bangladesh Government) in 1989. In that case, the Learned Judges unanimously ruled that the fundamental structure of the Constitution cannot be altered by the legislature. Since then, Bangladesh's Supreme Court has upheld this doctrine.

The Reform Commission has proposed substantial changes to the Constitution's basic structure, which would significantly alter its core characteristics. This raises the question of whether the commission has the authority to recommend such changes within the scope defined by the government. According to the Basic Structure Doctrine, even the legislature of Bangladesh cannot make amendments that alter the Constitution's fundamental structure. Implementing these recommendations would be a highly complex process, requiring the direct consent of the people. Without this consent, such fundamental changes would not be constitutionally valid.

Conclusion

The proposed changes to the Constitution carry immense significance. Omitting the Proclamation of Independence, introducing sweeping changes to the fundamental principles of governance, and replacing the final paragraph of the preamble with a new one go against the spirit of the Liberation War and could potentially lead to national division.

Bangladesh is currently undergoing a transitional period marked by political, economic, and social volatility. The economy is in turmoil, while an abnormal law and order situation raises serious concerns about public safety and security. Additionally, the country faces mounting pressure from geopolitical tensions and global uncertainty, which pose significant challenges to national stability and security.

In such a moment, it would be unwise to embark on drafting a new Constitution. Instead, the focus should be on fostering national consensus and strengthening democracy as a means to navigate these challenges effectively.

Golam Rasul, Professor and Chair, Department of Economics, International University of Business Agriculture and Technology (IUBAT). E-mail: golam.grasul@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Right On Schedule

The most eagerly anticipated, and frankly hyped up, announcement of an ...

Fighting raged along the borde ...

Fighting raged along the border of Cambodia and Thailand, with explosi ...

ICIMOD drives regional cooperation to inspire new mo ..

The Cage of Captivity and the Cry for Freedom: A Cru ..

Why Japan issued an advisory for a possible megaquak ..

The Autocrats’ War on Universities