Column

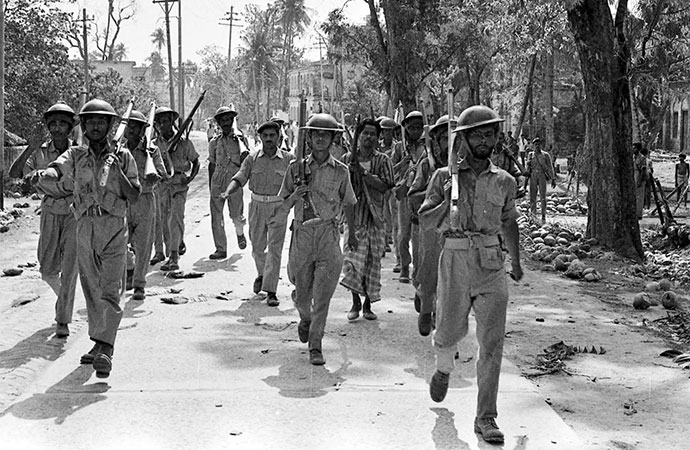

Troops of Bangladesh Freedom Army, followers of East Pakistan's Sheikh Mujibur Rahman march off to war against Pakistan Army troops, near Jessore, East Pakistan. File Photo: AP

Most narratives and discussions of 1971 begin and end with the State. That means it goes back to certain ideas and concepts that circulate around the primary governing institution that largely is run by the ruling class - the official world. In other words it means the government. That is built by several layers of legitimacy including the national sovereignty, supremacy of the three primary institutions - executive, legislative and the judiciary - to which is added the electoral voting process. Together they make up the state and it's this institutional experience that dominates the narrative of the State as the history of any event.

This dominance is taken for granted and the process also ensures the supremacy of the State. But whose state is it is a question which historians don't handle letting the Statist narrative roll over all others. This is not unexpected but the result has been the production of an incomplete historical narrative, leaving out more perspectives than including them. It becomes a limited historical reconstruction process.

The Statist framework

While the dominant presence is that of the Awami League as it is historically linked to the state construction process, first as Bengal Muslim league which was part of All Indian Muslim League which in 1949 became Awami Muslim league and later Awami league. This process is linked to the Lahore resolution of 1940, the ancestor of the current state framework, the independent state for dominantly Muslims of Bengal. This was amended by AIML to serve its political convenience. It was never part of a political consensus.

The process passed through many stages including the United Bengal Movement of 1947 - a byproduct of a fragile Bengal Congress and Bengal ML alliance - which the Pakistan leader Jinnah supported but Congress leader Nehru didn't.

In many ways therefore, 1947 was not a consensual independent State so it's no surprise that there was no support for the central Pakistan imagination. While February 1952 became the symbol of transition from the Muslim to Bengali identity politics, what remains less stated is that it was state making ideology led by the elite in all these cases. The electoral victory of Awami League in 1970 and later formation of the Mujibnagar government strengthens this assertion.

While that was the case with the main political party, AL wasn't the only claimant to the State making process. Every political party of various shades and colours including those hugely in conflict with the AL aspired for state power. Together the entire political spectrum may be described as the Statist caucus. It should be noted that within these parties there were various streams too including the AL and the Left. That is why the Statist narrative is also not monolithic though the aspiration was common.

Their interpretation is based on power relationships and the construction process of the State as the dominant historical reality. But it is a limited narrative.

The societal dimension

The other dimension of history is society. Fundamental to the understanding of the societal dimensions is the role of formal and informal socio-economic structures as it relates to State and society where the informal dominates. Almost all formal states are developed capitalist in nature and even the socialist Soviet Union too was before it collapsed under the weakness of its inadequate formality. The need to maintain an efficient formal economy put enormous pressure on the socialist State as its formal system was weak.

In the case of pre- capitalist economies, informality dominates. Much of the so-called South falls in that. The State is a governing mechanism that originated in the early days of capitalism and has continued till date and is now into another level of change under the regime of global economization.

For historians of 1971 that means locating the nature of the statist governing structure as well as societal structures and then exploring its history. What happens is that the state ruling class takes over history writing as it is its prime source of legitimacy and writes a particular version. Since regime changes are common, each state regime rewrites history to help gain that statist legitimacy.

A lot of that happens because in generally pre-capitalist economies society is almost invisible and self-sufficient. it doesn't require history for its legitimacy as its historically organic. Hence, it's easy to forget the societal aspects of any history. This is also made easier by the ideologies of historiography which includes written documents to qualify as a "historically legitimate" source. This virtually excludes the entire societal aspects of history unless observed through Statist eyes.

That applies to 1971 history too. The result is the absence of the role of society, and focus on the State although it acted from a position of weakness rather than strength. On the other hand society's role lay in its organic ability to survive and exert pressure on State institutions. While the Mujibnagar government was largely dependent on external States for its survival, societal constructs were not under any such pressure and the villages were equipped to survive. It also provided the "armed conflict" space which put pressure on the occupation forces. And it was acting on social impulses of survival not ideology.

Perhaps the most eloquent testimony to the role of society particularly rural/village society was made by the Chief of the Eastern Command of the Joint Forces of India and Bangladesh, Lt. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora to this writer who was talking to him as part of a BBC assignment. "Do you think the armed forces could have entered Bangladesh if its villagers did not permit them to do so.?"

It was not an admission of the gap that historiography of 1971 suffers from. Till the Statist narrative and the Societal narrative are integrated, historical analysis will remain incomplete.

One should also bear in mind that society operating on its own has done much better, withstood all pressures and Statist failures to sustain its informal nature yet flourish. The State component in comparison has not done well and is still unable to become efficiently formal and develop legitimate formal structures to survive in an increasingly critical state.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Another stress-test for the wo ...

And just like that, the world economy has been thrown into turmoil onc ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip ...

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan offered to mediate for a new ce ...

Bangladesh flags economic risks of prolonged Middle ..

Bangladesh seeks enhanced cooperation with Argentina

US trade deal discussed with BNP, Jamaat before sign ..

Road Transport and Bridges, Shipping, and Railways M ..