Column

Photo: wikimedia

Long ago, when I was an undergraduate student at Presidency College, Calcutta, I participated in a debate whose motion was: "The problem is that there is no problem." Luckily, I spoke for the motion, since those opposing it did not stand a chance of winning. Obviously, the motion suggested that the problem facing Indian society at that time - the year was 1974 or 1975 - was that many or most people believed that the system was fine on the whole and so all they needed to do was to survive and thrive in its spacious interstices. That is why India produced excellent doctors, engineers, lawyers, diplomats, administrators, and so on. Where, then, was the problem?

Those speaking in support of the motion argued that it was precisely this positivist attitude of accepting the rationale of a system, simply because it existed and produced excellence at its highest levels, that underlined the real problem: the problem of believing that there is no problem. What about landless farmers, industrial workers and unemployed youth? No problem? What about poor children who went to mediocre schools where they could never hope to become doctors and engineers one day? No problem there? What, above all, about women whose unrecognised labour at home was expended within patriarchal walls where they could be and were abused at will? No problem even there?

Indeed, there was a problem with the debate itself. It was an inter-collegiate debate conducted in English. Why was it that only the "good" colleges of Kolkata - such as Presidency, an elite of one (unless Calcutta Medical College was there as well, which I cannot remember) - were participating in this debate? Where were our shy peers from far-flung district colleges, whose language of reason and remonstrance was Bangla and not English? See, the problem was their absence but, then, absence cannot be seen: That is the problem. What you do not see does not exist: That is the problem with having no problem.

The motion was carried. It carried the day, and it carried the imaginative burden of my subsequent years at Cambridge and Harvard. Everywhere I went, there was no problem. Everywhere I went, I saw the problem with having no problem.

Nothing has changed fundamentally in the five decades from the day when I entered that fateful debate. Exclusion and marginality define the parameters of social existence around the world, but that is no problem because they do not affect the lifestyles of the talented and the successful, and their teeming global acolytes.

Bill Gates and Steve Jobs are among a handful of mythical figures whose exploits on the warring market for technology could have caused a new Iliad or Odyssey to be written, except that Classical Greek is so passé in the glitteringly demotic world of high finance. Where is the problem with that? If a problem exists, it does so only in the idle minds of airy-fairy intellectuals who have nothing better to do than complain about the world that they live in. Get real. Get going. Get a life. Preferably in Wall Street or Silicon Valley. But you studied English, and you, Sanskrit, and you, Bangla? Gosh, why ever? Give me a break. Get lost. What's your problem?

Ironically, Gates and Jobs would be among the first to recognise that there is a problem. It is that while the market is the best way to create wealth, it is the worst way of distributing it (because it rewards only winners in a Darwinian race that has no finishing line). And when wealth gets concentrated increasingly in the hands of an oligarchic few, the empty hands of the many reach out for countervailing change - whether in the form of fatalistic faith or atheistic armour. This is why enlightened individuals such as Gates and Jobs invest in social resilience through educational scholarships or the preservation of the public sphere by upholding the need for news without fear or favour.

Or consider the environment in its relationship to development. Who can complain about development, which is a process of economic evolution comparable to the ongoing biological evolution of humans from apes? However, when development challenges the biological integrity of the environment, its very capacity to sustain human life on earth, development becomes a vicious form of economic, social and biological regression. But that is no problem, since most of us will not be around to witness the human species' return to the economic equivalent of apehood. Walking on all fours when not swinging from tree to tree (should any poor tree still dare to exist), we shall be immune to the intellectual development of the human race that has been erased by the insane "developmental" attack on a sustaining universe.

The Anthropocene, defined as that swathe of time during which human activities have impacted on the environment sufficiently to cause distinct geological change, would have come to an end. Problem? No problem. At least not mine, since I won't exist. But others will. So, the problem is that there is no problem.

Perhaps the naysayers are right. A return to apehood would mean that no ape would carry out a terrorist attack on neighbouring apes terrible enough to invite a genocidal response. Nuclear weapons would not be used, since no ape would know how to use them. Religion would return to its rightful place in the beautifully irreducible mystery of being instead of being hijacked by common criminals and crowing clowns.

Then, there would be no problem.

But today, problems exist, and denying that they do so constitutes the chief problem of homo sapiens. Auguste Rodin's sculpture, The Thinker, provides the iconic signature of meaningful existence.

Why think when there is no problem?

The problem is that there is a problem.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow of the Cosmos Foundation.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

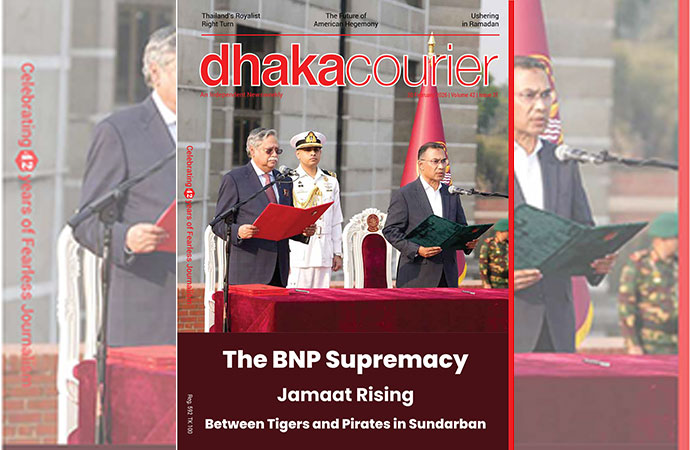

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury