Column

Anika Tasnim. Photo: Collected

Anika Tasnim has become one of the iconic faces of Bangla Basanta, the Bengali Spring that has unseated an autumnal government. Why not? Just look at her.

Her headband wraps the colours of the Bangladesh flag - the ardent red of the sun surrounded by the generous green of nature - around her. The headband announces her mythological entry to the lexical politics of Bengali destiny. The flag that she wears supersedes kapale lekha, that fate which is apparently inscribed on the forehead. She looks angularly upwards and leftwards to the skies, suggesting that whatever kapale lekha says can be overcome by chokher chaoya, the defiant turning of the eyes towards collective exigency. Her raised voice merges the contours of her sonorous being with the presence of the protesters gathered around her in seamless harmony.

Bengali womanhood gains renewed agency in her. Anika Tasnim is not plaintive: She does not ask for favours from an autocratic regime. She demands political recognition and acceptance. She reclaims her feminine/feminist self in the act of protesting against a patriarchal order carried out state-making on her stolen behalf.

And Anika Tasnim is beautiful, like Bangladesh itself. Actually, which Bangladeshi woman is not beautiful? However, Anika's participation in the protests gives the revolutionary moment a particularly erotic twist. There are many other women protesters, of course, but most are busy denouncing the state of affairs. That is good, but Anika's iconography is different: Just her face suffices as her claim to revolutionary fame. She is relentlessly beautiful, as relentless as the youthful protesters' stubborn demands that finally lead to the overthrow of a geriatric regime.

Revolutions are nasty affairs: They are not beautiful. They cut humans down to their basics by unleashing biological conflict among classes. Revolutions destroy known epistemologies: They bring in other categories of knowing, becoming and belonging. Bangladesh's revolutionary moment has been extremely incendiary, naturally.

However, it has been said that humans cannot bear too much reality - too much change too soon. That is why a figure of continuity, so long as it looks to the future, comforts people. And nothing is as reassuring as the continuity of beauty.

That is Anika Tasnim's ideological contribution to Bangla Basanta. "Bangla will remain Bangla. Look at me," she seems to say. "I am beautiful like the future of Bangladesh."

Barthes' Anika

Life thrives on images.

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes writes about the fabled face of Greta Garbo. "Garbo still belongs to that moment in cinema when capturing the human face still plunged audiences into the deepest ecstasy, when one literally lost oneself in a human image as one would in a philtre, when the face represented a kind of absolute state of the flesh, which could be neither reached nor renounced. A few years earlier the face of Valentino was causing suicides; that of Garbo still partakes of the same rule of Courtly Love, where the flesh gives rise to mystical feelings of perdition." Barthes concludes his essay by remarking that the face of Audrey Hepburn is an Event, but that of Garbo is an Idea.

Anika Tasnim's face is both an Event and an Idea. In the words of an author, Barthes' Hepburn represents a "grounded, tangible presence that is tied to particular moments, roles, and experiences". By contrast, Garbo's face "projects a sense of timelessness, mystique, and unattainable perfection"; it is abstract, symbolic, idealised, mythical, archetypal and almost goddess-like. Anika is both. Like Hepburn's face, she relates herself intimately and decisively to moments, in her overwhelming case a revolutionary moment. Yet, in the far distant look of her questing eyes, she holds a vision of Bangladesh as a nation of perpetual revolution. Fighting the next revolution could well be more difficult than having won the last one.

If anything, Anika Tasnim's face bears political comparison with that of Che Guevara, who in several accounts has been described as "the rock-hero biker revolutionary", "the martyr to idealism", and "James Dean in fatigues". Che became a visual symbol of student rebellion during the May 1968 protests in France because of the global reach of a photograph of his taken by Alberto Korda in 1960 titled "Guerrillero Heroico", which was turned into a facial depiction by the Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.

I do not know whether Anika has Che-like ambitions, but what I know instinctively is that neither she nor Bangladesh will return to the moment before she appeared on the visual stage of the world with her headband. In an instant, and for a long political time to come, she became the aesthetic representative of Bangladesh's uneasy young who want a new order to replace the fallen old.

I do not know whether she belongs to a political party, and I do not wish to know. I do not know whether her viral fame will domesticate her into serving the visual needs of voyeuristic males and envious females. That would be a tragedy. Someone who can embody the spirit of females who are both feminine and feminist should not seek refuge in fame, which is what the powerful dole out to ambitious women to co-opt them into the workings of an ultimately patriarchal order.

What I know is that Anika Tasnim is the face of the new Bangladesh. It will remain beautiful so long as she stays young. Biologically, people grow old. Politically, though, youth is. a matter of choice, not destiny. There is no kapale lekha. There is only chokher chaoni.

Look at the world to come, Anika, and await its arrival.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow at the Cosmos Foundation. He can be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

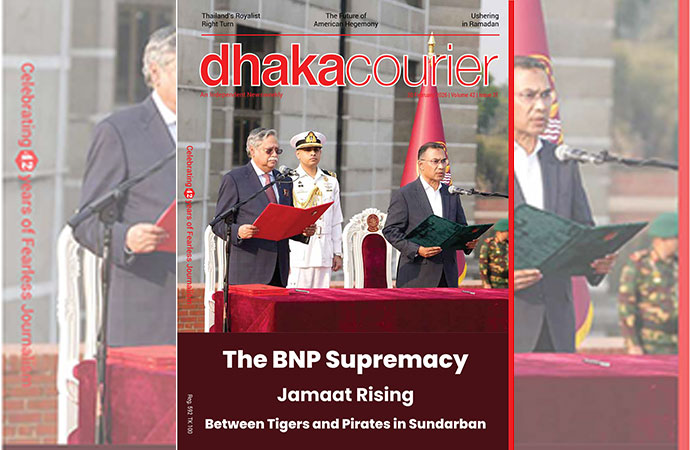

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury