Column

Photo: AP/ UNB

Bangladesh had its second revolution in July last year, the first having occurred in 1971 of course. What might 2025 and the years to follow hold for the nation?

One way of answering is to place Bangladesh in the global trajectory of revolutionary nations. Indonesia would make a good starting point for comparison.

In 1965, the Indonesianist Clifford Geertz edited a book of essays, Old Societies and New States: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa. As the title suggests, the quest for modernity in the new states produced by decolonisation was hampered by the cultural inertia of old Asian and African societies. Geertz was not wrong. His article in that book, "The Integrative Revolution: Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics in the New States", laid prescient emphasis on what is called identity politics today but was in the 1960s the way in which development "exacerbated rather than mediated ethnic, religious, and linguistic claims to loyalty and jurisdiction", in the words of a fellow-scholar.

Then, in 1983, the Indonesianist Benedict Anderson published an article, "Old State, New Society: Indonesia's New Order in Comparative Historical Perspective", in which he pointed out the paradox of postcolonial states pursuing "internal and external policies remarkably similar to those of their colonial predecessors, despite the passage from colonialism to independence". The paradox is "best resolved by focusing on the distinct, long-standing, institutional interests of the state-qua-state", in one description of Anderson's argument. Anderson turns the semantic tables on Geertz, blaming the state and not society for being old and celebrating society and not the state for being young.

Anderson shows how former Indonesian President Suharto's dictatorial New Order state was actually very old in its colonial provenance and how it managed to reverse the course of the new Indonesian society that his predecessor President Sukarno had sought to inaugurate by combining in his Nasakom ideology the three primary social forces prevailing in Indonesia: nationalism, religion and communism. In pursuing his argument, Anderson periodises the nature of Indonesian political development, from the growth of the Dutch colonial state; to its decline and near-collapse between 1942 (the Japanese invasion of Indonesia) and 1965 (the downfall of Sukarno's Guided Democracy); and its revival under Suharto.

Suharto fell in 1998 when the Asian Economic Crisis subverted his international pretensions to power, and a new generation of Indonesians, tired of his ailing rhetoric of building a new state on the ruins of an old society, destroyed his domestic pretensions to power. Suharto's old state was overthrown by a new society. Sukarno was dead by then, but he must have smiled from his grave. Suharto had destroyed Sukarno's new society with the help of the old state: Now, the Indonesian people had destroyed Suharto's old state with the help of the new society - their own.

Except for the departure of East Timor (now Timor Leste) and the religious autonomy granted to Aceh within the nation, Indonesia has not fragmented. Suharto's military dictatorship has not been recreated; neither have Muslim extremists taken control of the world's most populous Muslim-majority country. Decentralisation of power from the capital Jakarta to the provinces has helped to bring the world's largest archipelagic nation (with 17,000 islands) closer politically. Most important of all, the return of power to the Indonesian masses appears to be irreversible. Indonesia's second revolution of 1998, after its first on independence from the Dutch in 1945, is safely in the hands of the people.

That is how it should be.

Bangladesh

Where might the Bangladesh revolution of 2024 lead?

My short reply: Bangladesh (just as the Indonesian variant of revolution has led to Indonesia). My longer reply: Any revolution has three phases: disruption, consolidation and continuity. Bangladesh is undergoing the first phase. The Awami League's rule has been overthrown, leading to perhaps the greatest disruption in Bangladesh's history since its freedom from Pakistan in 1971. Students, workers, job-seekers and many others are making demand upon demand on post-Awami Bangladesh, incessant demands that reflect the changed distribution of power in a society in creative turmoil. The interim government is popular and respected, but it is a government after all. No government can meet all the demands of the people, certainly not completely and all at once. This first phase will continue till national elections are held, and elected political representatives negotiate with voters on the best direction ahead.

Consolidation will appear with the formation of a new government composed of political parties that will indulge in Politics, which is the art of allocating scarce resources among various stakeholders: workers, farmers, students, employers, religious and secular organisations, the military, and so on. This second phase will determine the economic and political viability of the 2024 revolution. If consolidation is not achieved, the old forces will return in new form, or new insurrectionary forces will make a bid for power. Forces of religious obscurantism and regression are never to be disregarded: They know how to hide their true colours till it is time to show their bloodied hand.

Assuming that consolidation works, continuity will be the next frontier for Bangladesh. In continuity, democracy will be the baseline of national politics. No one will be able to make a mockery of it through farcical elections or confessional politics. There will be political competition - which is the main point of democracy - but it will not be hijacked by parties promising salvation in the next world so long as people vote for it in this world. The way in which the Awami League co-opted elections was truly bizarre, but the way in which religious extremists could use elections to come to power and then strangle democracy is not only bizarre but frightening.

Indonesia has entered the third revolutionary period of continuity. That is heartening for fellow-Muslim-majority Bangladesh. Bangladeshis are not a lesser people than Indonesians. There is no reason why Indonesia can have a successful revolution and Bangladesh cannot. But the choice rests on Bangladeshis.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow of the Cosmos Foundation. He may be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

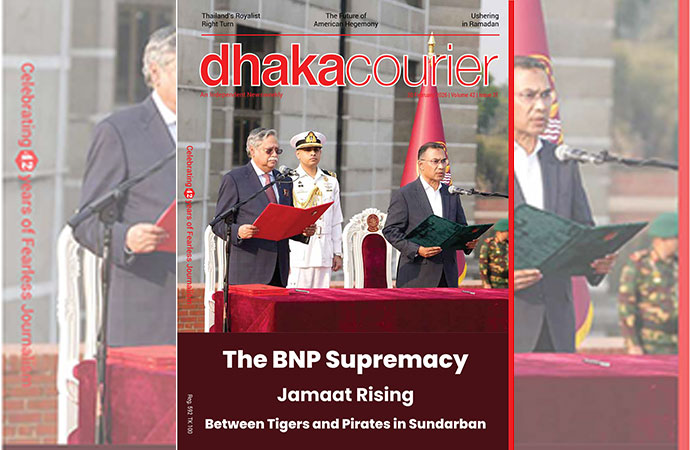

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury