Column

Freepik

I began my career in journalism-specifically, English-language journalism-shortly after completing my university education in 1991. I studied Mass Communication and Journalism at Dhaka University. Although I was not the most dedicated student, I made an effort to grasp the fundamentals of communication and journalism.

Understanding how journalism is a form of communication was a foundational concept. Journalism is indeed mass communication because, by sharing essential information with a broad audience, a media outlet engages with members of society, keeping them informed about events within the country and around the world.

The essence of communication reveals that journalism is a significant social responsibility. This responsibility entails upholding the core values of journalism: accuracy and fairness, if not objectivity. Objectivity, often seen as a relative concept, has its own controversies-whether human beings can ever truly be objective. I won't delve into that debate here.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have asked how I view journalism. I usually respond with deep frustration, as I feel what we practise now is not true journalism. Journalism has lost the dignity it once held in society. Information can be shared with the public in various forms and styles, yet the essence of honest journalism seems diminished.

People, as masters of language, are adept at shaping incidents to serve their own agendas within news. Just as poets write about love and women in their unique words and expressions, humans have refined this art over time. If a poet employs this skill to spin a tale that may not be factually true, it is often celebrated as creativity, the strength of the writer's imagination. The more vivid the imagery, the greater the admiration it evokes from readers, hence it is called literature-a realm of imagination.

But can a journalist do the same? Can a journalist depict an event with their own twists and embellishments that stray from the truth? The answer should be no, but sadly, journalists in Bangladesh and around the world have done just that for quite some time. An incident is often narrated through personal angles and agendas, and Bangladeshi journalists are no exception to this trend.

There was a time when journalism was guided by social commitment and responsibility. Not anymore. Nowadays, it often aligns along political lines, with journalists divided accordingly.

After more than three decades in journalism, I find myself wondering: what is journalism, anyway? What sort of communication are we providing to society? How are we supporting the public in building a knowledge-based society where justice and reason prevail, rather than the dominance of particular groups or individuals?

In the lead-up to Bangladesh's 2024 national election, I observed senior journalists discussing their organisation's policies on political issues. A senior colleague presiding over the meeting asserted that there was no harm in a media house supporting a political party, pointing out that this occurs in the United States. While there is some truth to this, the fact remains that the standard of American journalism is often far ahead of what we see in Asia. Quality work and well-supported evidence can bridge the gap in some cases. However, pure activism driven by press releases and unfiltered rhetoric cannot be called journalism.

The corporatisation of journalism has dealt a severe blow to the profession everywhere. Now, everyone talks about views, while few discuss the responsibilities of journalists or the obligations of media houses to serve the public good.

Recently, I was reading Maulana Abul Kalam Azad's 'India Wins Freedom'. In the first chapter, he describes how, in 1913, he pioneered modern Urdu journalism and endured imprisonment repeatedly for speaking out against British rule. Journalists in Bangladesh, too, have faced imprisonment over the decades, contributing to the country's welfare and society's betterment.

Today, journalism has become a cheap and unremarkable job, largely due to the rapid advancement of technology, which has made media projects far less expensive than in the past. In Bangladesh, the number of web portals now exceeds that of journalists, and many of these portals are little more than propaganda machines.

In Bangladesh, there are also journalists who secure newspaper licences through political connections, only to sell them for millions of taka for personal profit. In a democratic country, publishing newspapers and launching web portals is not a problem. However, there should be no compromise on journalistic values and principles.

I am reluctant to call journalism a noble profession, but it is certainly a respectable one, like many others, where professionals carry out their duties and serve the country. Those who work in law enforcement and medical fields are similarly doing vital work, as long as they uphold honesty and professionalism.

There is no denying that journalism is also a business, but that business should not be conducted at the expense of honesty and authenticity. Journalism thrives on undistorted facts and accurate storytelling. In the name of journalism, there should be no character assassination, invasion of privacy, or deliberate attacks on individuals through the presentation of unverified facts.

When I find myself lying awake at night, I ponder the terms and concepts of journalism, such as 'Objectivity,' 'Authenticity,' 'Press Freedom,' 'Communication,' and 'Mass Communication'. Yet I cannot arrive at a clear understanding of these words. Today, I am genuinely confused; tomorrow, I may be even more so.

Mahfuzur Rahman is Editor UNB.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

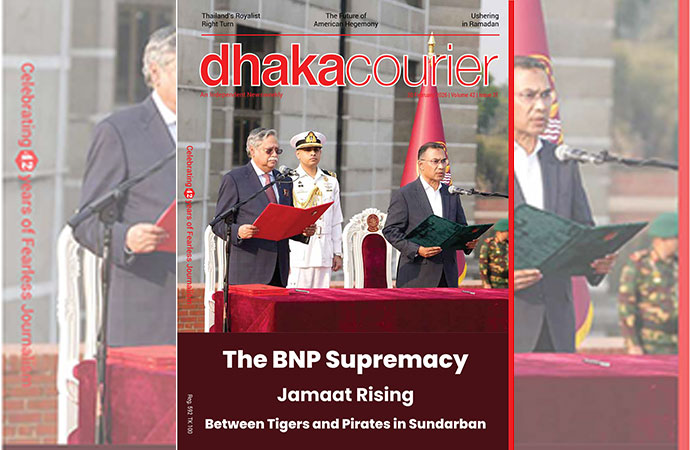

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury