Column

Image: Collected

UNESCO's decision to adopt February 21 as the International Mother Language Day in 1999 marked a degree of global recognition for a day in 1952 which proved to be a turning point in Bangali history. What was till then a linguistic demand for Bangla to be accepted as a state language of Pakistan along with Urdu - a demand that was successful ultimately in 1956 - led to a broader movement in East Bengal under the leadership of Maulana Bhashani of the Awami League. Other instances of discrimination practised by the western wing of Pakistan against the eastern wing, primarily in matters of the extraction and redistribution of economic resources; and in the inequitable distribution of political power, resulted in the Six-Point demand for East Pakistan's autonomy presented in 1966. Rebuffed, that demand grew into a quest for independence that culminated in the epiphanic Liberation War of 1971.

As a student of history, I am trained to not believe in counter-factuals (that is, ideas such as "if that had not happened, this would not have happened"). Thus, would be wrong to say that if the language protesters had not been martyred in 1952, Bangladesh would not have been liberated in 1971: There are simply too many causal gaps and indeed breaks in the intervening two decades for anyone to make such a claim. But what did occur, and what is true, is that, in 1952, the Bangla language turned from being merely a means of linguistic communication into a means of political communication as well. Thenceforth, to speak Bangla was to make the political statement that Pakistan did not consist only of its Urdu-speaking elite in a western wing made up of Punjabis, Sindhis, Balochis, Pashtuns and others (demographic remnants of the Turko-Afghan ruling class in North India that had imposed its rule on undivided Bangla during unhappy centuries); but that Pakistan, should it really wish to be a homeland for the Muslims of South Asia, would have to include the legitimate linguistic, cultural and economic aspirations of Bangalis in the eastern wing, which in any case was more populous than the western wing. There was nothing wrong with being a descendant of Turko-Afghans: Bangla's own population bore witness to that genetic mixing produced by history. However, it is one thing to be a biological part of an ethnic mix, and another to try and dominate it in the name of a racist and supremacist ideology.

Unfortunately, the tendency of politicians and policy-makers in West Pakistan to equate East Bengalis' love for Bangla with the Bangla spoken by East Bengali Hindus - and, by imputed and illogical extension, with the Indianness of West Bengali Hindus - apparently diluted the core "Pakistani-ness" of East Bengali Muslims. Such convolutions produced expected results: the break-up of Pakistan just 24 years after its own secession from India.

The Language Movement was the catalyst in the linguistic/political reimagination of Pakistan that led to the dissolution of that country. Today's Bangladesh owes to it the homage of history: "Amar bhaiyer rokte rangano Ekushey February/ Ami ki bhulite pari?"

My Ekushey Legacy

The mother tongue is not just another tongue. People are capable of learning many languages, some, indeed, with which they become more familiar than they do with their mother tongue. The Indian cultural stalwart P.L. Lal once said that Punjabi was his mother's tongue but that English was his mother tongue. I understand that sentiment perfectly. In my own case, I took to English with effortless ease because it was spoken by my essentially adoptive father, a Malayali, whose only means of communicating with me was in his Oxbridge English. But I spoke Bangla with everyone else in my family. English came to be my chosen language of cultural affiliation and economic sustenance. From my Honours in English at Presidency College, Calcutta, to my M.Litt. in History at Cambridge as a Chevening scholar, and to my Fulbright visiting scholarship at Harvard, I have been a part of the English-speaking world. From Calcutta's The Statesman to Hong Kong's Asiaweek and Singapore's The Straits Times, English has fed me, and continues to do so through the Dhaka Courier today. What do I not owe to English?

Most of me, of course, but not all. Bangla has made me worthy of English, as is the case the other way around. It is in Bangla that I learnt to look around as an infant for my parents, to hunger, to hurt, to cry, to eat, to pee, to potty and to leave it to my family to clean up the royal mess after the Bengali me.

And I wasn't even born in East Bengal, where, at the moment of my birth in 1957, I would have inherited the legacy of the language martyrs whose blood had ensured that every Bangali child would possess the right to speak in Bangla. To those giants of life and death I owe the pride that I feel even at the smallness of my Bangali existence, expressed in English.

That's me. Many humans are larger than me. The Oxford historian Tapan Raychaudhuri's autobiographical Bangalnama celebrates the depth and reach of his Bangal (not just Bangali) provenance, as does the Cambridge economist Amartya Sen's Home in the World, which bears testimony to the capacity of language to bridge and even overcome religious divides. Both Tapanbabu and Amartyada share with me the happy fate of having entered the creaking gates of Presidency in the formative youth of our international years, and all three of us emerged with a sense of Bangla's ripening agency in our departing years - they much more than I, of course. None of us would have achieved our intellectual fluency in English without our familial fluency in Bangla.

So, I owe my authenticity as a Bangali to the martyrs of the Language Movement. This year, as in every year to come in the Bangali calendar, so long as I live, I shall pay homage to the international lineage of Ekushey.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow of the Cosmos Foundation. He may be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

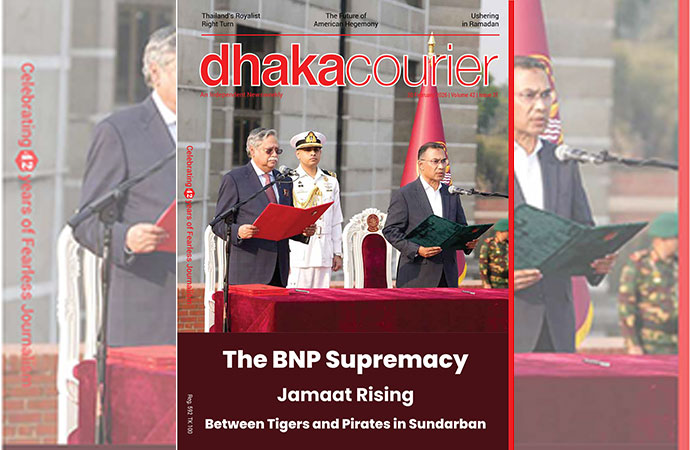

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury