Column

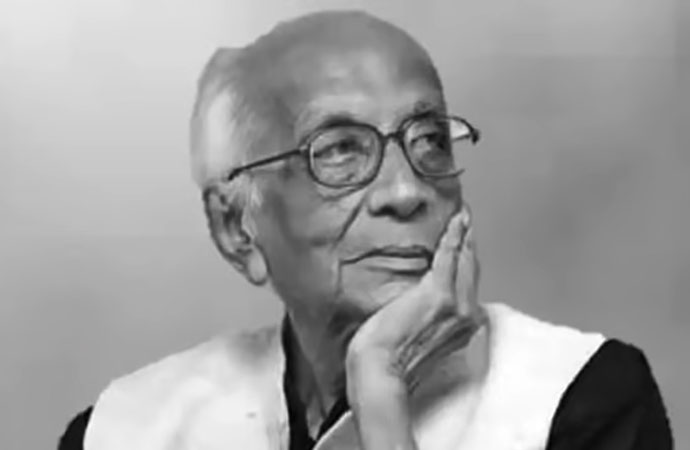

Nirendranath Chakraborty. Photo: Collected

Merry Christmas!

I mean it. Here's why.

Nirendranath Chakraborty's poem, Kolkatar Jishu (Calcutta's Jesus), pays homage to Jesus Christ as the child-Saviour who is transported from his birth in Bethlehem to an imagined infancy in the capital city of Bengali misery and pride. Nirenbabu's poem might well have been called Dhakar Jishu, for Kolkata and Dhaka are but each other's counterparts; all other cities pale by material or metaphorical comparison to rival Kolkata and Dhaka in their mutual recognition and rejection across a common national border. After all, Nirenbabu (1924-2016) was a pan-Bengali poet, having been born in Faridpur but having reached the culmination of his poetic life in Kolkata. Banglar Jishu - Bengal's Jesus - is thus a figure who represents the transformative agency of liberating spiritual power in an imagined united Bengal.

A free-wheeling translation of the poem would read thus: "There was no red light, but storm-paced Kolkata the city came to a stop unsuspectedly. Taxis, cars, three-wheelers and tiger-stamped double-decker buses waited in precarious but obedient balance. 'Gone, he's gone!' shouted those on either side of the street as they rushed forward - load-carriers, hawkers, shopkeepers and buyers all - before they froze like figures on an artist's easel. All watched in desperate awe. For he was crossing the street on his unsteady and uncaring two legs, a naked little boy. It had rained just a while ago on Chowringhee. Now the longest shaft of sunlight pierced the heart of the clouds to descend on Kolkata to swathe the city in wondrous hues."

This is a socialist epiphany, for Nirenbabu was to poetry what he was to the Left: all of himself. That poor, naked little street-child, for whom no one stops, stops time in its tracks when the poem rescues him from the everyday anonymity of his disregarded existence the moment he decides to cross the street in defiance of the oncoming traffic. Then, cars and buses stop for him; bystanders cry out; he keeps walking; and a poem is born. It would have been the same poem in across the border. Dhakar Jishu would have survived as an emblem of a Bengali sensibility with participating Christian provenance much as Kolkatar Jishu does.

Thinking of Jesus as a Bengali is not sacrilegious because the reach of his love and power knows no borders. Not only Christians but any humanist who understands the redemptive role of Christ in the unfolding of historical time would understand that he is a defender of the deprived, the challenged, the marginalised, the victimised and the desperate. Such are the humans who people Bengal, and the most vulnerable among them are the very old and the very young. The little child in Kolkatar Jishu embodies a biological vulnerability - he is naked - in the face of a hostile environment. In the child's persona, the Palestinian Jesus becomes the Bengali Jishu. Bengal enters the endlessly generative repertoire of Christian thought, which spread from Bethlehem and Jerusalem to Europe and the rest of the world to make Christianity a great world religion. Today, it is the religion with the largest number of followers. Christians in Bangladesh and West Bengal belong to a global family. They bear witness to the beautiful and kind glory of Christ.

A message of love

In my own reading of the Bible, a reading that is superficial no doubt but is deeply felt all the same, the chief difference between the Old Testament and the New Testament is the nature of human transformation presented through the figure of Christ. In the Old Testament, God is essentially the ultimate Law-Giver whose writ and will can be disobeyed only by inviting the torments of life Here and the terrors of Hell in the Hereafter. So it is in the New Testament, but now there is the added reassurance that there is someone who can hold the mortal's hand and lead him to Salvation because that someone - Christ - is a sacrificial figure, one sent by God to die on earth so that fallen humans may be saved. The Son of God becomes the Son of Man so that man may reach God. And the path is one of love. It is Christ's love that transforms Old Testament time to New Testament time.

Today, the affairs of the world are as much, if not more, an affront to the love that Christ embodies as they were in his time. Herods abound. All of them fear the Kingdom of God because they think (and rightly so) that it will overthrow the Kingdom of Man. Like the original Herod, they fail to understand that Christ did not come to be King of Men. He had no need for that crown. But the Roman Empire not only crucified him but mocked him with a crown of thorns. The Romans thought that they had taken care of him forever. Little did they know that their forever was but a laughing caricature of the true forever, which is marked, Cross-like, by the redemptive suffering of a man whose realm was filled by men, women and children seeking eternal peace through seamless justice here on earth and beyond.

Kolkatar Jishu brings the heavens down to Bengali earth. Crossing a Kolkata street or a Dhaka street in heavy traffic is akin to the pilgrimage of the soul from this world to the next. Kolkatar Jishu crossed over safe and sound.

That is why he is called Jishu.

The writer is Principal Research Fellow of the Cosmos Foundation. He may be reached at epaaropaar@gmail.com

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Auspicious beginnings, but a l ...

The newly elected government of Bangladesh is now in office, and the e ...

Caught between tigers and pira ...

Over 10,000 fishermen in the Sundarbans have suspended their fishing a ...

Historic Chawk Bazar comes alive with iftar items on ..

Shaping Young Conservationists: School Conservation ..

Iran has said it has reached an understanding with t ..

New Finance Minister Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury